Lattepanda Iota SBC Review: The Intel N150 Shines

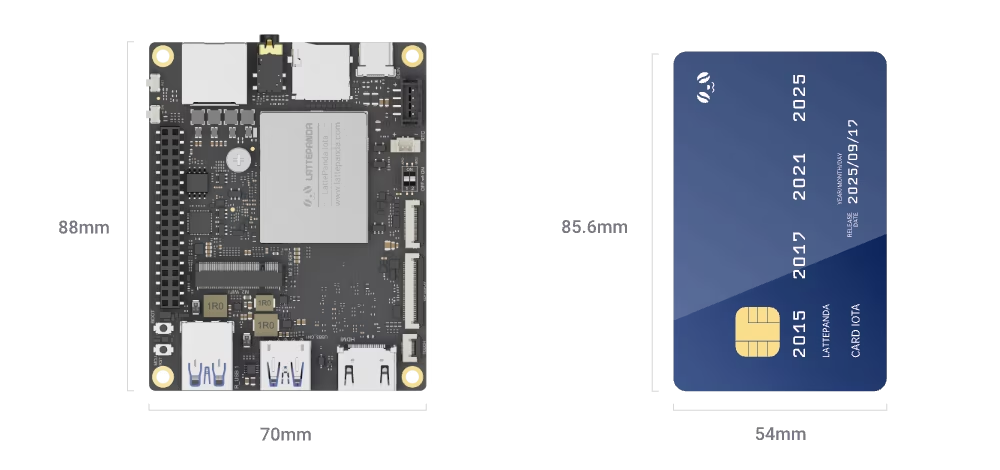

We’ve been reviewing a bunch of SBC in the past couple of years, starting with a focus on the Risc-V architecture, before going to ARM64 and now are back full circle with the Lattepanda Iota SBC which is Intel based (we still have more reviews coming up). Size-wise, it follows the credit-card standard proposed by the original Raspberry Pi, and still retains GPIO headers.

It is based on the Intel N150 processor with 4 Cores/4 Threads (no hyperthreading - which is similar to what we find on ARM). We were provided a review unit by Lattepanda for this review (the 8GB RAM version) - just because we were very interested to have a final say on this important question: around the same price point, what can you expect from an ARM64 SBC and Intel-based SBCs in 2026? Any clear winner?

Specs on paper

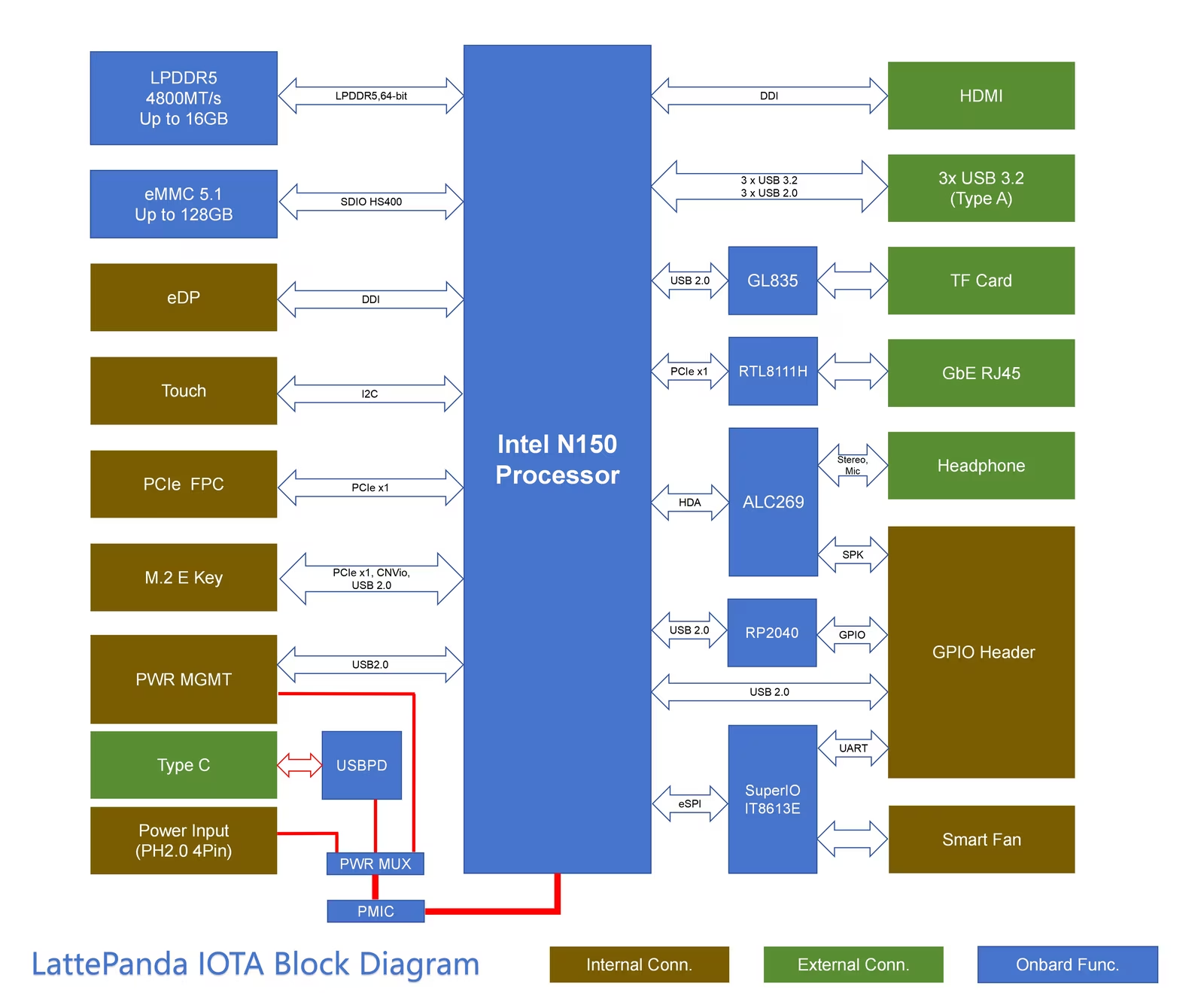

Here’s the full specs for this SBC.

| Component | Specification |

|---|---|

| Processor | Intel® Processor N150 |

| Graphics | Intel® UHD Graphics 730 (24 Execution Units, up to 1 GHz) |

| Co-Processor | RP2040 MCU (133MHz Dual-core Arm Cortex-M0+, 264KB SRAM, 8MB Flash) |

| Memory | 8GB / 16GB LPDDR5 4800MT/s (with In-band ECC) |

| Storage | 64GB / 128GB eMMC 5.1 |

| Display Output | 1x HDMI 2.1 (Up to 4096 x 2160 @ 60Hz) 1x eDP 1.4b (Up to 1920 x 1080 @ 60Hz) |

| Networking | 1GbE RJ45 Port (Supports Wake-on-LAN) |

| USB Ports | 3x USB 3.2 Gen 2 Type-A (10Gbps) 1x USB 2.0 Pin Header 1x USB Type-C (PD 15V Power Input Only) |

| Expansion | M.2 E Key 2230 (PCIe/CNVio) PCIe FPC Connector (PCIe 3.0 x1, 16-pin) TF Card Slot USB 2.0 |

| OS Support | Windows 10 & 11, Ubuntu 22.04 & 24.04 |

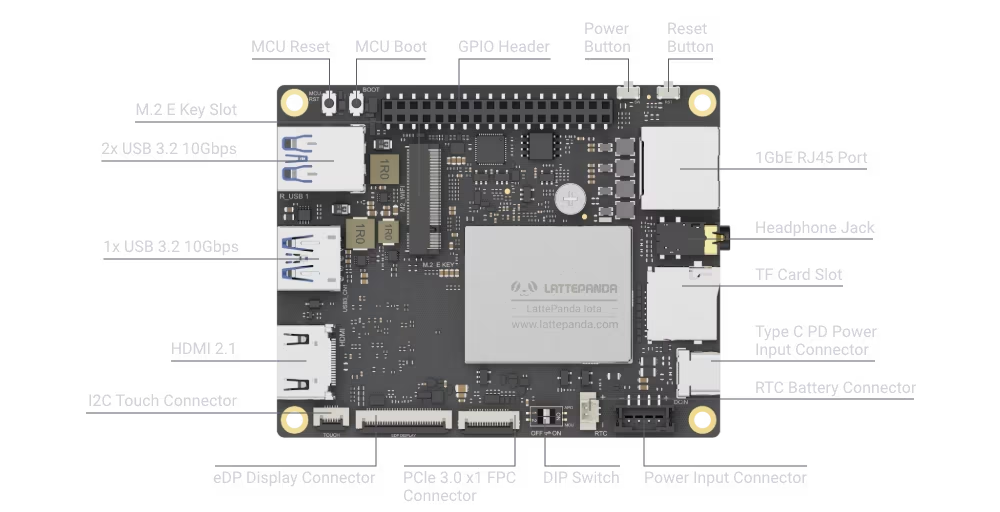

And here’s a quick overview of how the ports are configured:

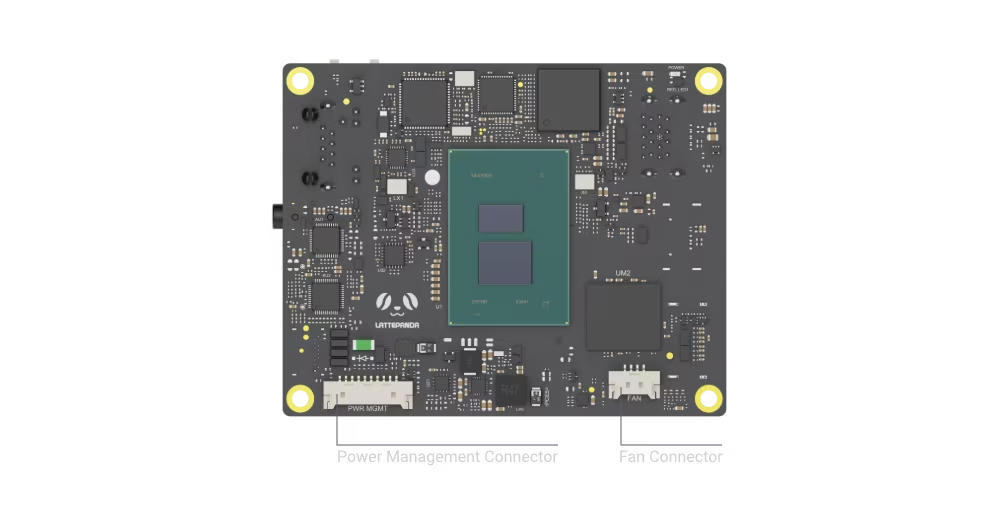

And the back side of the SBC.

One of the main drawbacks of this board is in its I/O capabilities. Both the M2 2230 and the M2 extension board connect with PCI3.0 (single lane only!), which cripples data transfer between the CPU and such drives. It will still be fast, but nowhere what you get with PCIE4 lanes in comparison.

| Interface | Active lanes | Theoretical Speed |

|---|---|---|

| PCIe 3.0 x1 | 1 | ~0.985 GB/s ~1 GB/s |

| PCIe 4.0 x4 | 4 | ~1.97 GB/s ~8 GB/s |

In theory you will be limited to 1GB/s. That sounds like a lot, but in practice, even “budget” NVME drives nowadays usually hit around 5,000 MB/s, so this will definitely impact every performance. It won’t impact so much boot times for example (since this is random access more than serial), but when loading large files (for example in games), I suspect load times increase will be fairly noticeable.

One more detail - as you can see we have GPIO pins on the board, and this is something that is ultimately controlled by an additional RP2040 MCU integrated on the board. The RP ensures compatibility (as far as I understand) with the Raspberry Pi controllers, and is supported by micropython code or Arduino C++ code. You can see below how the GPIO headers are shared across components on the SBC:

Since I’m not really into electronics, if you are interested to know more about how this works, they have a section on their wiki related to RP2040 MCU programming.

All the ports and interfaces make that board fairly flexible for a wide range of applications: home automation, robotics, IP cameras, Edge machine learning applications (detection, monitoring, etc) - and of course it’s powerful enough to run a full fledge Linux desktop system.

Assembling the board

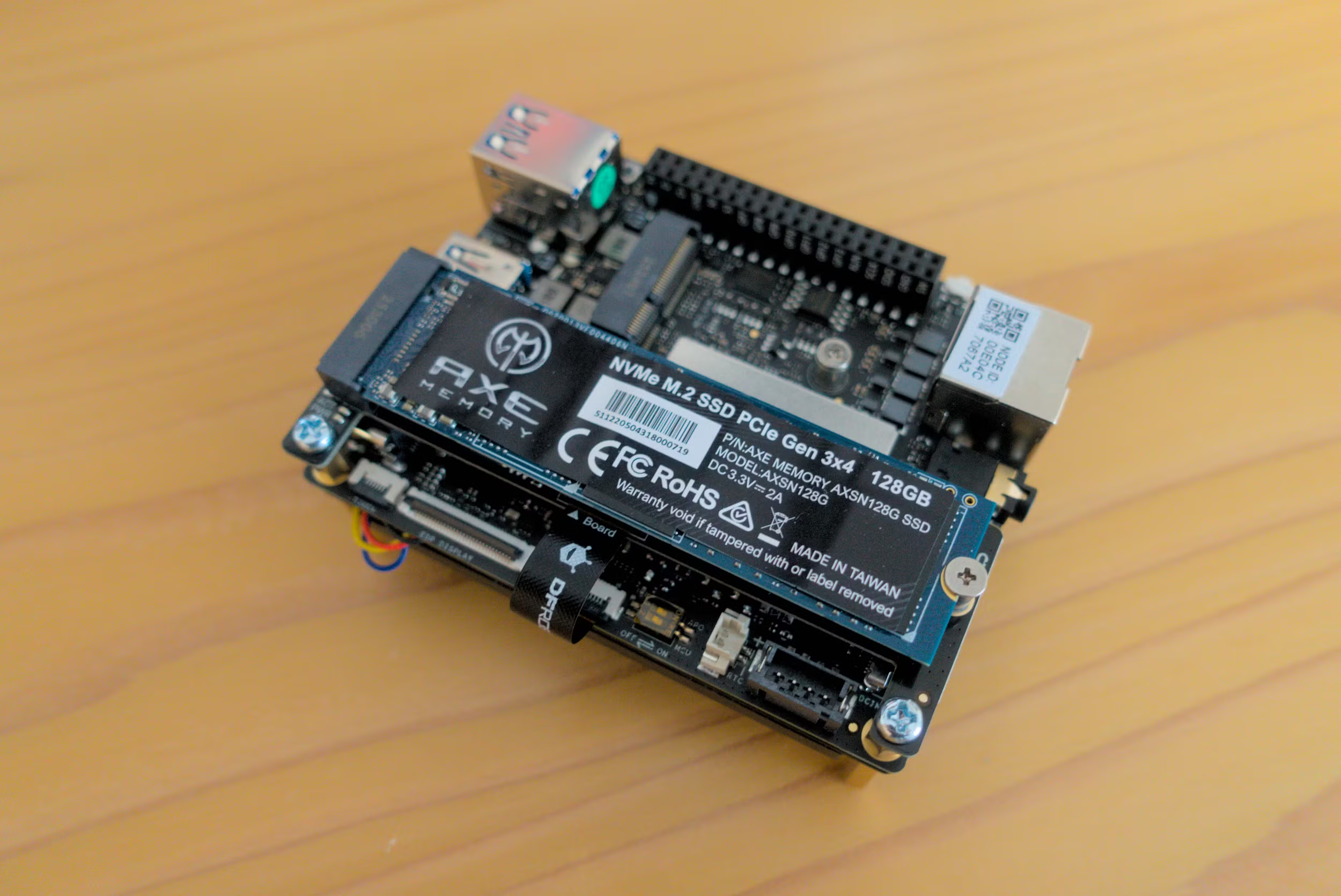

This is not completely plug and play. You get a few components to assemble.

Since this is X86_64, you’ll need some active cooling, and the board comes with a fan shield to attach on the board. You’ll need some thermal paste as well to ensure the CPU has proper cooling, and 4 screws to bring the fan shield and the board close to each other’s. Nothing too difficult, it’s a matter of 5 minutes.

Once you are done, you can also install the M2 NVME extension board on top of the main board to give you a proper storage option (2280 NVME drives). You have a small connector between the main board and the extension board to make it possible, as well as 2 screws to make it more stable. After that, you can install your 2280 NVME drive. Another 5, 10 minutes of work.

Last but not least is the battery that will keep your board on time even when turned off. Not mandatory to run your board, but recommended if you don’t want to rely on an internet connection for the time information.

It’s probably not going to be for everyone, but it’s also possible to power this board through Ethernet using an expansion board. Which is pretty cool and gets you rid of the USB cable for power.

You need to have a switch or a router that supports the IEEE 802.3bt standard for it to work. Typically this means more expensive router or switches, not the run of the mill consumer stuff you get at the lowest pricing.

BIOS

You get a fairly complete BIOS with this board, with a bunch of standard options. Of particular interest are the TDP settings. By default they are set between two limits, 10W and 20W. For maximum performance it is recommended to set the lower limit at 15W. In practice it does not seem to change the performance massively, but it allows the board to over above the 10W limit when needed. A 10W limit seems to enforce more drastically a return at 10W TDP as soon as possible after a deviation.

Note that if you want to use a passive cooler instead of a fan, it is recommended to lower the TDP to 6W with an upper limit of 6W as well. That does not seem to be a good idea unless you want to run the board off the grid, on batteries.

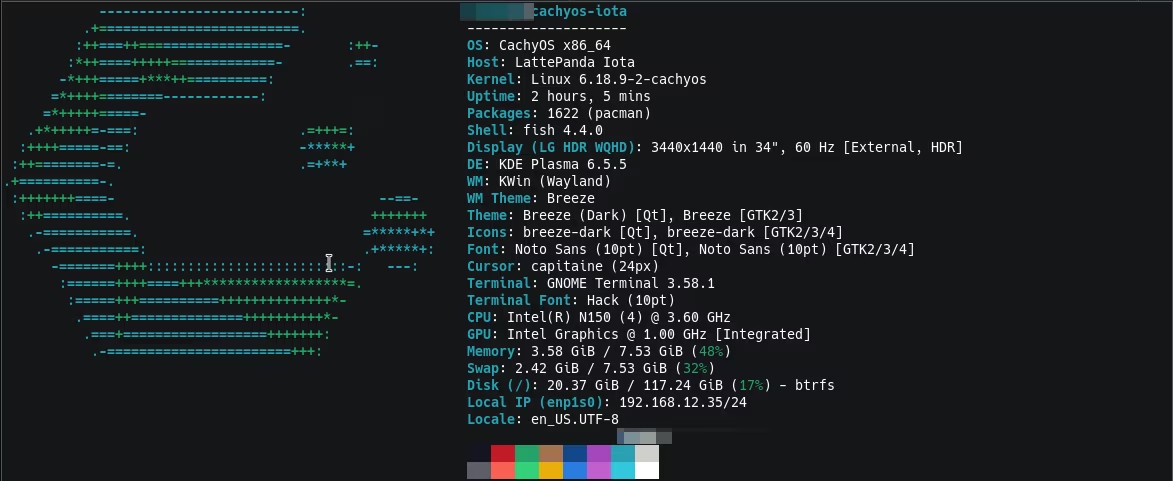

Software Support: Going with CachyOS

Since we are on good old X86_64 architecture with a proper BIOS to interface with the hardware, we don’t really have to wonder what is going to work on this. A regular CachyOS ISO booting on USB works wonders to get to an installer, and 30 minutes later here I am with a glorious Arch-based Plasma Desktop (or GNOME if you prefer).

Needless to say, running on X86_64 makes things very easy when it comes to switching distros.

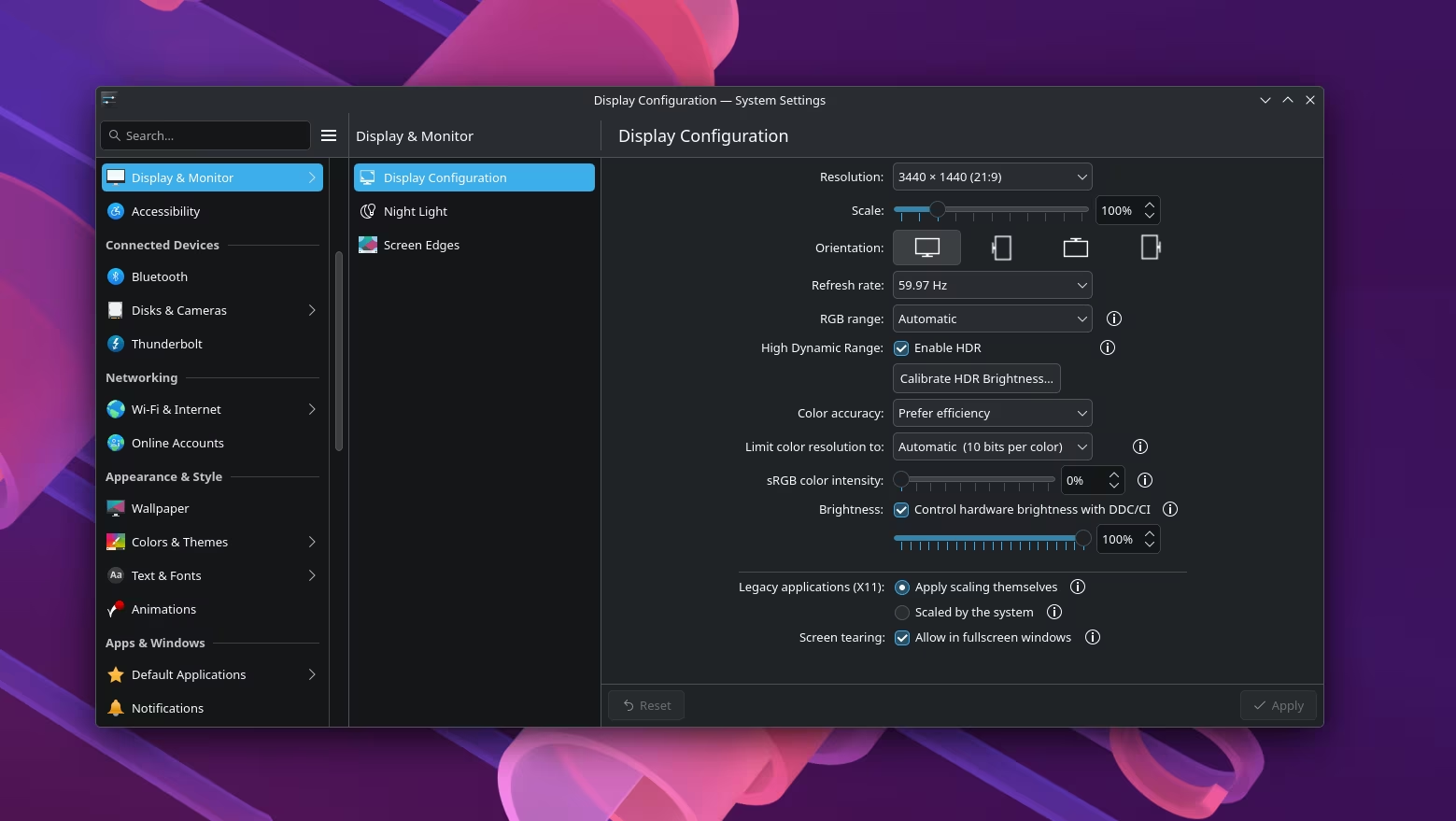

Desktop Experience

With CachyOS, I land into a KDE Plasma desktop, that works as expected. Fast, reactive, with proper hardware support as far as I could tell. The Vulkan acceleration is working well, too, and can be confirmed easily with tools like vkmark. We now have good HDR support on the desktop directly in modern kernels and desktop environments, and this board has all the hardware and ports to make it work.

OBS also directly recognizes QuickSync support for video encoding acceleration, which is great. Don’t expect to be able to record a gaming session at the same time with OBS, though. If the GPU is heavily used, QSV will drop a lot of frames.

While I did mention that the PCIe port was limited by a single line, it’s hard to see a clear difference when just using the desktop, since most of the I/O access is going to be random access. So in practical terms, unless you are reading big files at once, the lack of PCI4 is not so meaningful on the desktop.

Performance

My main interest is about the performance of that board. What can we expect nowadays from the N150, and how does it compare, for example, with the recent OrangePi 6 Plus ARM64 board that we just reviewed?

Geekbench

Geekbench 6 gives us some indication on what we can expect in terms of overall performance. Here are the overall results, with comparisons with the OrangePi 6 Plus, the OrangePi 5 Ultra and the Raspberry Pi 5.

For more details you can see the Single-core performance for each SBC.

We can see that the N150 is doing very well, single-core wise. However, as you can imagine, with only 4 cores, it suffers the comparison with SBCs that have a lot more cores:

In a nutshell:

- The Lattepanda Iota is definitely much faster than a Raspberry Pi 5.

- Its single-core performance is very good, at the same level of what you see on the OrangePi 6 Plus which is a beast.

- When looking at multi-core workloads, the OrangePi 5 Ultra matches its performance, and the OrangePi 6 Plus goes far beyond.

Since most workloads are usually driven by single-core performance, this is a very fast board all things considered.

Video Encoding / Decoding

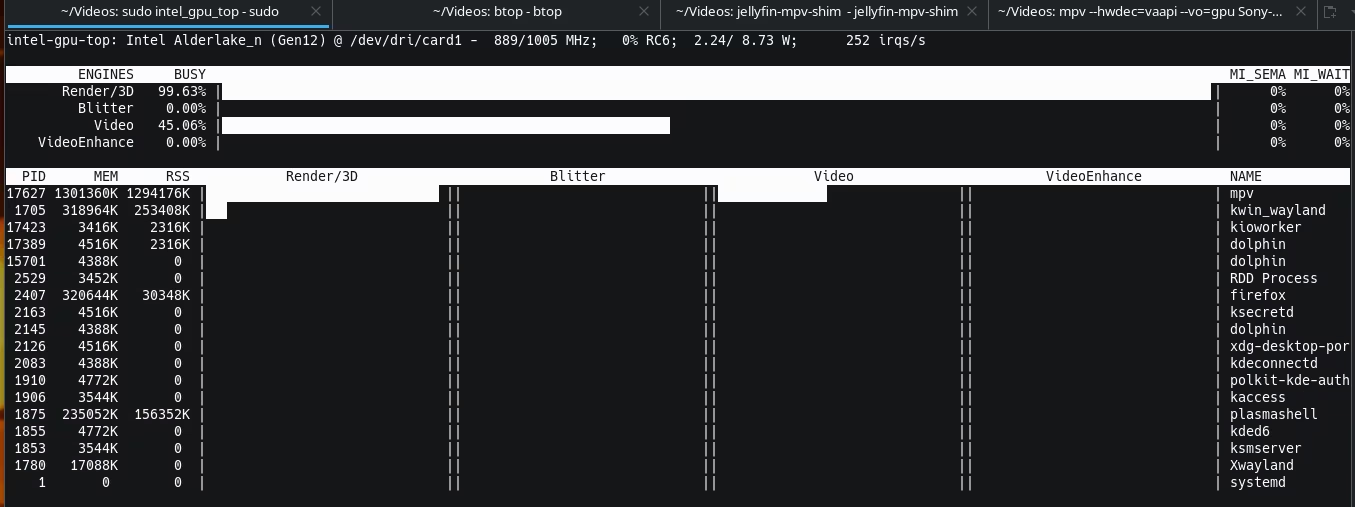

This deserves a whole section to itself. At first I was not too impressed by the default capabilities of video decoding in the browser (despite numerous tweaks in Firefox, I still get dropped frames in videos). It’s usable but not exactly great. The main point was to figure how to make local video acceleration work well, through mpv. You need to ensure that you have the latest drivers installed for intel hardware support, of course. And you also need to tell mpv to use vaapi for hardware acceleration, so that it tries to use the intel specific hardware decoding capabilities.

mpv --hwdec=vaapi <videofile>

But even that was not enough. The monitoring tool btop clearly showed that the GPU was maxing out at close to 100% usage, which sounded like Intel was either doing some false advertising about the hardware capabilities, or we had a problem somewhere. The nice little tool intel_gpu_top was extremely useful to understand where the bottleneck for smooth video playback was.

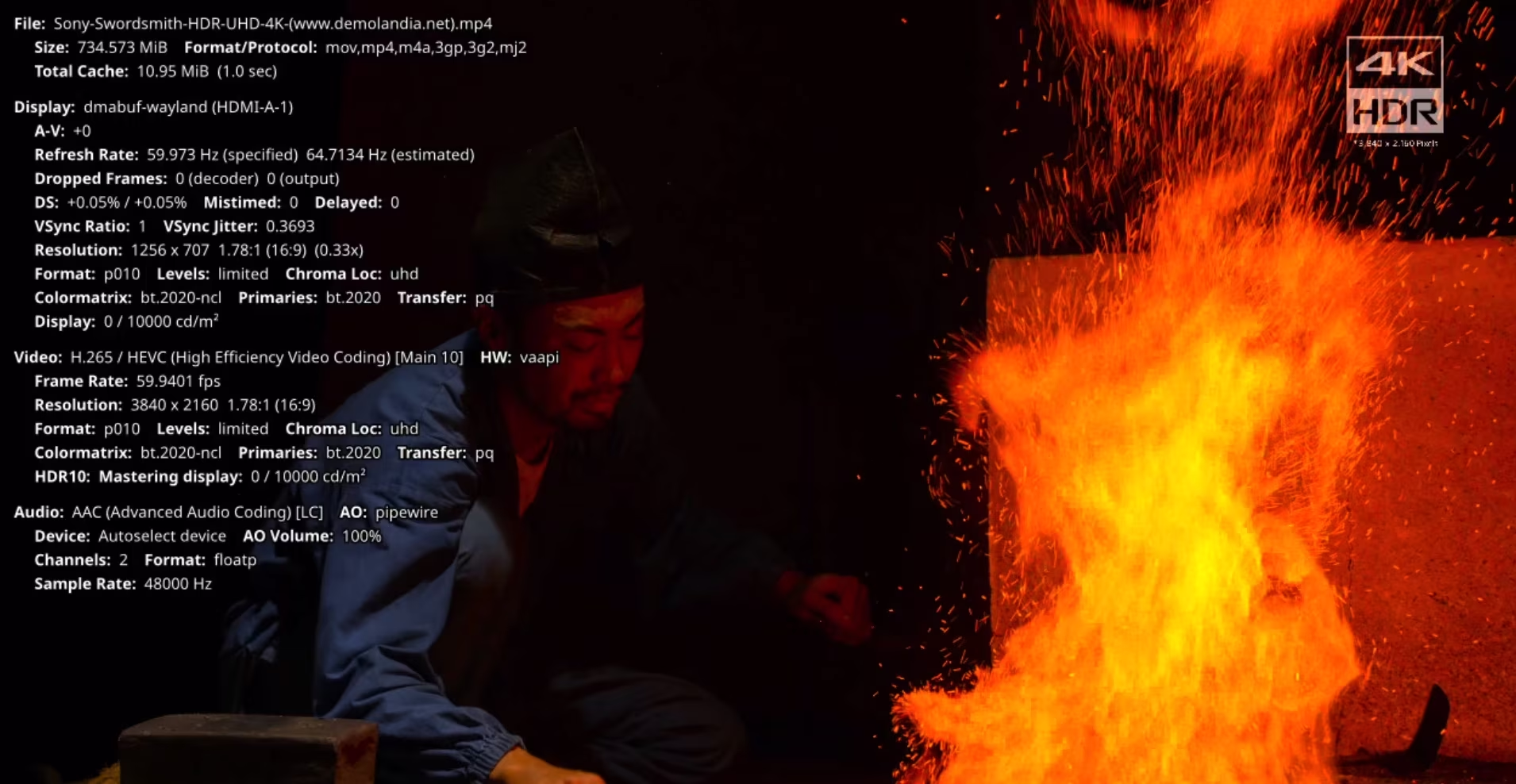

Turns out, the decoding part of the video was working as expected, i.e. it could decode a high quality, HDR, 4k 60 fps video stream without a sweat, but the rendering of pixels was causing a bunch of frames to be dropped. It’s not like video playback was choppy - overall you were not too far from 60 fps, but the rate at which frames dropped make it very obvious, even for an untrained eye, that there was something wrong.

Turns out that a few things needed to happen to improve dramatically the render time: switching the output to dmabuf-wayland to skip any screen copy and go direct to rendering, and using a fast profile to avoid time-consuming post-processing.

mpv --hwdec=vaapi --vo=dmabuf-wayland --profile=fast --gpu-api=vulkan <videofile>

Once this was done, we get to a frame perfect 4k HDR 60 fps video decoding, and the GPU is not dropping frames anymore (unless you move your mouse around on purpose). I reapplied the same settings for jellyfin-mpv-shim and tested it with my jellyfin server, and indeed 4k movies now were displayed just as they should, with pure hardware decoding doing all the work on the Lattepanda SBC. Extremely impressive.

That’s for the decoding part.

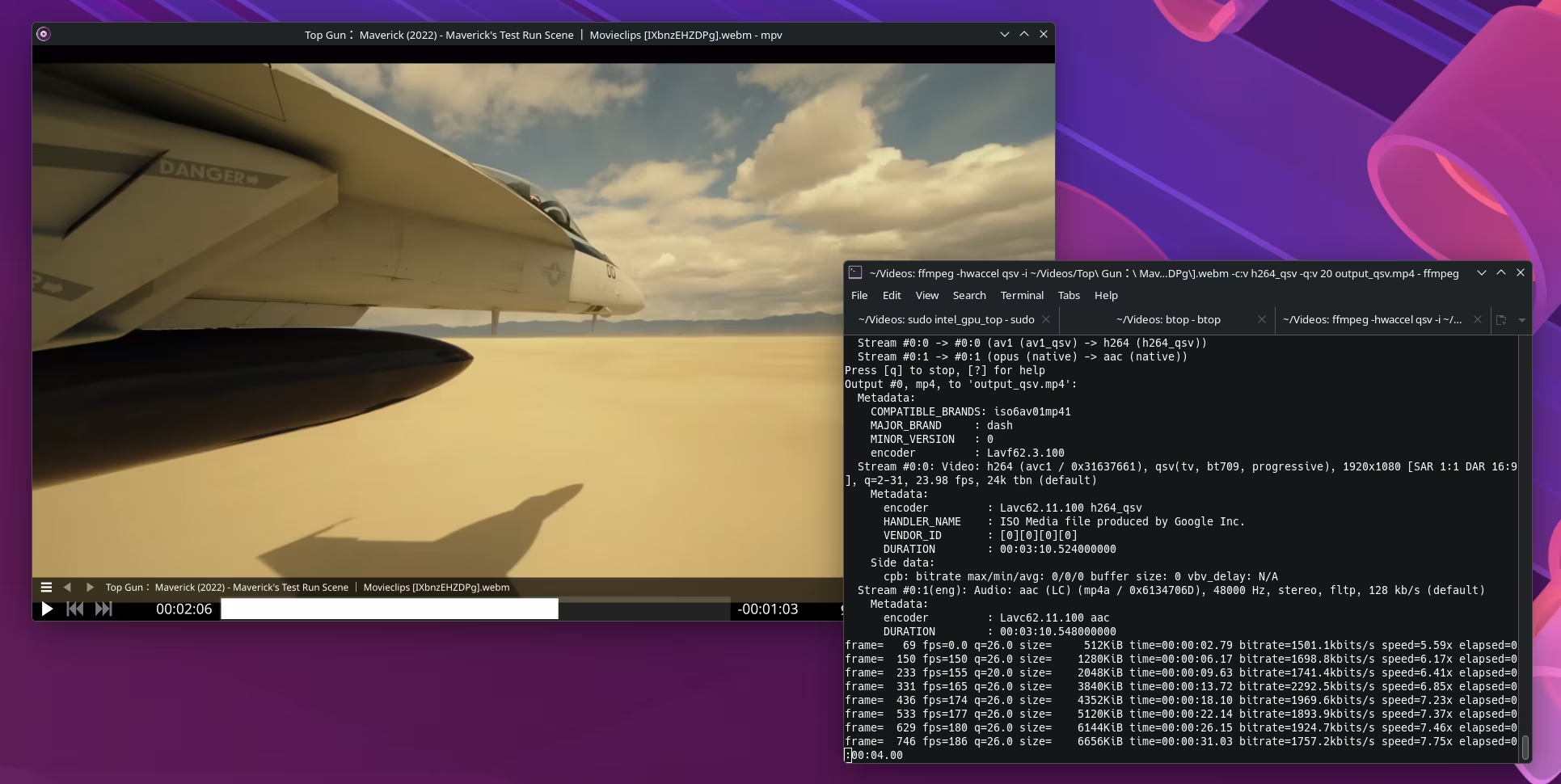

Then I tried the encoding capabilities with Intel Quicksync Video (QSV). You will need to install a few libraries to make it work, and potentially a full version of ffmpeg to ensure it was compiled to support it.

# make sure your user has access to the video group

sudo usermod -aG video $USER

# additional libraries, just in case

sudo pacman -S libvpl vpl-gpu-rt intel-gpu-tools

Here’s the command you need to use to make it work:

ffmpeg -hwaccel qsv -i <videofile> -c:v h264_qsv -q:v 20 output_qsv.mp4

The result is spectacular: you can compress a high quality video stream at 6x real time speed, with a fairly good quality preserved in the process using specific the QSV hardware. And this occurs at very low wattage!

You can confirm that the output file was encoding using qsv by using ffprobe:

ffprobe <videofile>

And it should show somewhere that the encoder Lavc62.11.100 h264_qsv was used.

Needless to say, if you are building a video client or a video server, this board is very, very desirable because of such characteristics.

LLMs with llamacpp

With the current llamacpp git repository (branch 0c1f39a9a (7999) release), you can compile Vulkan support for this board to hopefully get some good LLM inference performance that would not require the CPU to run at 100% day and night. At the end of the day this works, but the performance is probably not where we’d like it to be.

| model | size | params | backend | ngl | test | t/s |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| qwen3 1.7B Q4_1 | 1.06 GiB | 1.72 B | Vulkan | 99 | pp512 | 111.64 ± 0.62 |

| qwen3 1.7B Q4_1 | 1.06 GiB | 1.72 B | Vulkan | 99 | tg128 | 8.66 ± 0.21 |

Additional details: ggml_vulkan: 0 = Intel(R) Graphics (ADL-N) (Intel open-source Mesa driver) | uma: 1 | fp16: 1 | bf16: 0 | warp size: 32 | shared memory: 65536 | int dot: 1 | matrix cores: none

With Qwen3 1.7b model, at Q4_1 quantization, you get about 7 to 8 tokens/s on a mostly empty context. This is not great, and definitely not something that we could consider for a useful local or remote LLM server. Ideally you’d want a small model like that to run at 20 or 30 tokens/s.

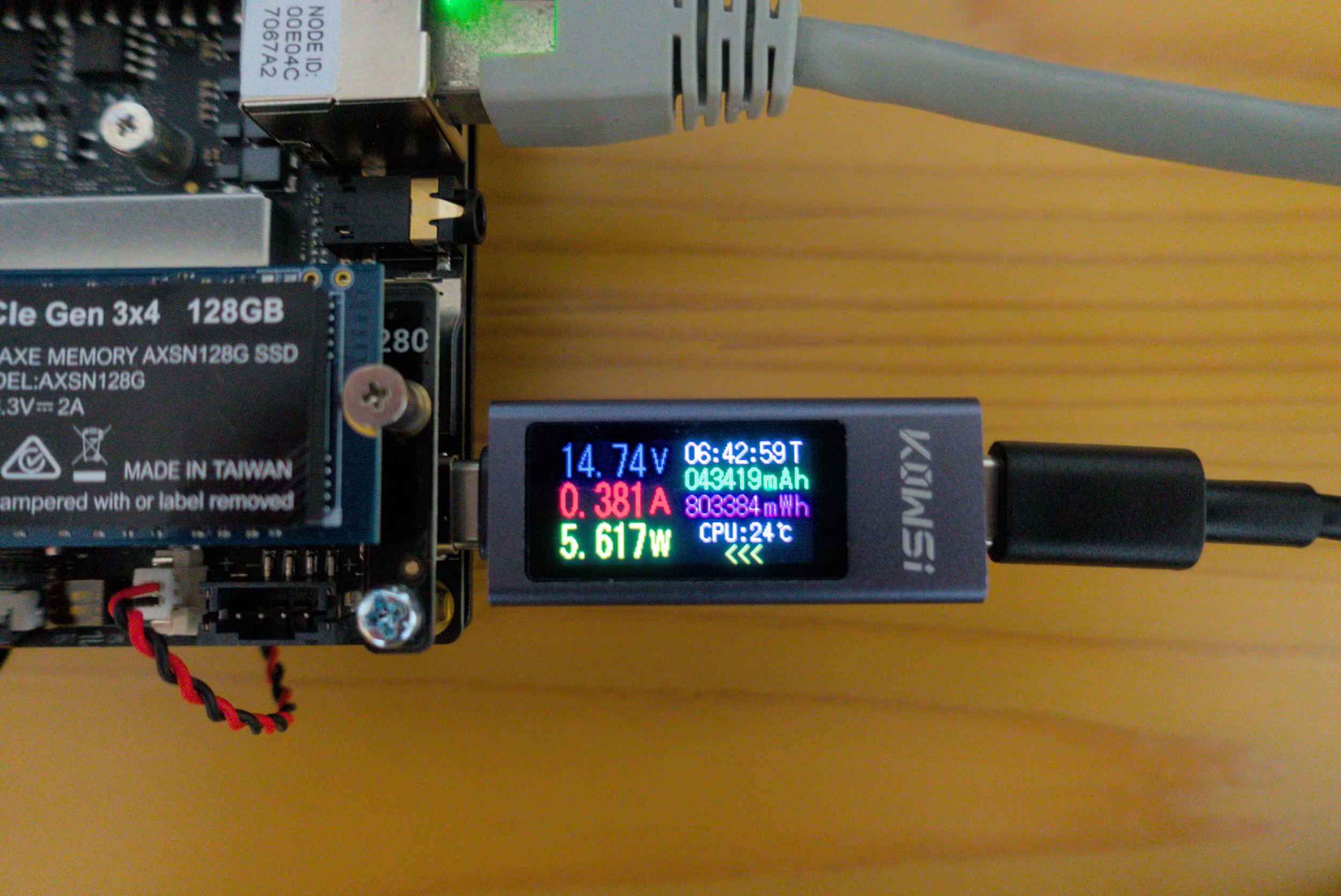

Power Consumption

Overall, very reasonable. When idle, along with a display connected, it’s between 5W and 7W on CachyOS. When doing some tasks and letting the CPU do its work, the consumption overs at around 15 to 20W. (do an example with compilation, and short video)

It’s possible to buy an expansion board to run the SBC on batteries only, which could be helpful for robotics or edge applications. On a battery pack you could be running for about 8 hours on that kit.

Noise profile

We are not in ARM-land here, and you should expect the fans to spin more often than not. It’s not that bad. But still worse than what I have seen on ARM64: the OrangePi 5 Ultra runs fanless without a hitch (so, perfectly silent), and the OrangePi 6 Plus, which is much more powerful, has pretty big fan unit that is fairly quiet overall. No miracle there, the bigger the fan, the quieter it is, so for the Lattepanda Iota, I don’t think they could have done much better with the small footprint available.

Gaming Experience

This is another topic of intest for us. Can we get this nice little SBC to run some games effectively?

FOSS Games

You can start with a couple of FOSS games that have native Linux builds. Oad is a good candidate and works OK, at about 30 fps in the tutorial, at 1080p and medium settings.

If you like financial management games more, OpenTTD can get you covered, and it works very well too, as expected, because it’s very light. Here’s a map in Antartica for a change.

So far, so good. Let’s look at how commercial games fare.

Light gaming

First starting with pure 2D games, with Blasphemous 2. Hard to believe, but we can’t even reach 60 fps at 1080p, we are somewhere between 40 and 50 FPS most of the time.

Continuing with Cat Quest 3, a 3D game with relatively light graphics, we can reach an OK framerate.

And then we have Dredge, a game we really liked a few years back, that should run well even on modest hardware, but here again we get between 20 and 30 fps at 1080p.

I also tried Cult of the Lamb, and from there it’s downhill. It’s a game that does look rather simple but is way more demanding that it seems (someone forgot to do some optimization…). And the result it not very impressive. At 1080p, with Low settings, I can hardly get to more than 15/20 fps in the base building area.

As expected, Intel integrated graphics does not perform great.

More demanding games

I tried some older AAA games, such as Bayonetta, and the performance at low settings in Full HD was far from spectacular. We are in the slideshow range, between 10 and 15 FPS, at low details, 1080p.

Similar observation for Civilization V, at 1080p, medium details - this time it’s playable because it’s not an action game, but the framerate is still pretty low.

Overall anything with too many shaders and polygons is going to make this SBC kneel down. This is what we expect from that generation’s integrated GPU capabilities: good for desktop use and video, but pretty weak when it comes to gaming performance, unlike AMD’s APUs.

Emulation

So as we can see, playing Steam games is not so convincing, but emulation has more potential.

I did not try too many of them, but PPSSPP gave me good results; it was able to run Wipe-Out Pulse at 1080p (4x the PSP resolution) with a steady 60 fps. It’s not an impressive feature, but at least this opens up a lot of doors in case you want to play some retro games on this SBC.

While I did not test other systems, you may have some luck to get decent framerates with Doplhin too, to run Gamecube and Wii games. Anything more recent than that is going to be a stretch.

What is this SBC good for?

This can be used in many ways. As a light desktop driver, this is a great little SBC. You won’t crush benchmarks but for browsing, Youtube, and regular applications this will work just fine. This is also a great little board to do some video compression, since you have hardware Intel Quicksync dedicated to video encoding and decoding (as long as you use a ffmpeg version that supports it).

However, forget any hope related to using this for gaming. The integrated GPU does not have enough muscle to deliver a good experience there beyond simple 2D games.

LLM support wise, same conclusion: do not waste your time trying to set this up as a some kind of small LLM model server. The performance is just not there. To seek more speed you’d need to look at onnx or OpenVINO alternatives, both of which requires models to be customized to run.

For server use, this is a great little board. It has a relatively low idle power consumption (5 to 6W), and is the ideal board for a local Jellyfin server thanks to the afore mentioned Quicksync Video capabilities that make it a breeze to re-encode a video on the fly while streaming it. Speed wise it won’t win any award but for a typical, local home sever you will be able to do an awful lot with this. Running Nextcloud, file servers, media servers, etc… The x86_64 landscape offers tons of possibilities with dockerhub.

I also find the help pages from Lattepanda docs to be well designed (all in HTML, with fairly clear references, and good explanatory pictures) which is a plus compared to having a large PDF to go through. They could benefit from a few added tutorials to also give the community some clear use cases to get started with (especially on the GPIO support side).

Choosing a SBC: ARM64 or Intel?

The eternal question! There is no huge performance difference between the two architectures these days, so ultimately what matters if the software support and what you really need. An Intel-based SBC gets mainline support and the latest kernels, while on ARM64 you are relying on the goodwill of the manufacturer to offer a recent kernel and distro image. In that sense an Intel or AMD hardware will always be superior, it’s not even comparable.

However, hardware wise, a board like the OrangePi 5 Ultra is more complete - it has a large M2 port available by default, Wifi and BT directly on the board, does not need a fan to function, and consumes less power overall.

There is no way to get the best of both worlds. ARM64 gives you a better performance per watt on paper, but is held back by the limited software support (you are stuck with the distro images provided by the manufacturer). Having an older kernel support on ARM64 is not a huge issue if you are running it as a server. Many servers run on older kernels and stable Debian distros that are usually several years old. Specific server software can be installed via Docker and not be restrained by your OS libraries. Or better, compiled Go binaries are very portable and can run pretty much everywhere independently from your distro’s age (almost). So, personally, for general purpose server use, ARM64 boards have a good value proposition. And provided you wait long enough, there is a good chance that they end up being supported by mainline Linux down the road (not full hardware support, but sufficient for what you need for a server).

There is an exception to the above statement. If you are building a server and you intend to use it for video streaming, a board like this Lattepanda Iota is going to be one of the best choices, because of the Intel Quicksync video capabilities. As we have seen, video encoding capabilities are really strong and ideal for a Plex or Jellyfin server.

If your focus is the desktop environment, I would also wage that an Intel-based or AMD-based SBC is probably a winner. The wider software support, the latest Linux kernels, the ongoing updates to newer distros, will give you a lot of reasons to prefer this archtecture! Frankly for most day-to-day browsing and applications this Lattepanda Iota is perfectly capable and fast enough.

This outcome, this moat is the result of dozens of years of efforts by Intel and AMD to ensure that their hardware is well supported on Linux, on and on. On ARM64 the only serious contender is Raspberry Pi, which has great software support, but its hardware is clearly behind what this SBC or other ARM64 SBCs can offer, so it’s not even a good competitor.

Alternatives for the N150 SOC

In this space there are a few other competitors that provide N150-based SBCs:

- The ECM-TWL-150N board from BCM, but is much bigger (and not yet available)

- The X104 from Nexcom, much bigger too, marketed toward the entreprise sector

- The QBiP-N150A from Gigaipc, again tailored for enterprise customers.

- The PICO-TWL4 REV.B in a slightly smaller format than the above options but still bigger than the LattePanda Iota.

Radxa has a N100-based SBC in a similar format, the Radxa X4 but they have not upgraded it to the N150 so LattePanda is definitely ahead.

At this stage, it seems that the Lattepanda Iota is almost unique in its category to provide a N150-equipped SBC in such a small, credit-card sized format.

Where to purchase the board

There are probably many resellers, but you can look at DFRobot as the official source for this hardware. Right now at the time of writing we have the following offering:

- LattePanda IOTA Palm-sized x86 Single Board Computer (Intel N150, 8GB RAM / 64GB eMMC) at 129 USD

- LattePanda IOTA Palm-sized x86 Single Board Computer (Intel N150, 16GB RAM / 128GB eMMC) at 185 USD

Note that you need to add to add 12 USD if you want the active fan cooler (recommended!). And you’ll need the M2 extension board to connect a full fledged 2280 M2 NVME drive (SATA drives are NOT supported), which goes for 12 dollars.

So it brings you to 153 USD for the 8 GB version and 209 USD for the 16 GB version.

If you need Wifi and bluetooth, that will require yet another small M2 Wifi board for that. Looks like the B200 Intel Wifi / BT version is a good match, and goes for another 20 to 25 USD.

Add all of this up - a full system will cost between 170 USD and 230 USD depending on the amount of RAM you want. I thought that this was more expensive than the equivalent ARM64 OrangePi 5 Ultra board (which has a similar performance profile), but in the meantime the prices for the OrangePi 5 Ultra have increased and they are above 200 USD for the 16 Gb version as well. So, no big difference.

If there is no difference in pricing, for most use cases, I’d probably prefer to go with this N150-based board instead of a ARM64 one like the OrangePi 5 Ultra. However, if you need a lot more performance, and don’t mind something slightly bigger format wise, the OrangePi 6 Plus currently at 250 USD (16GB version) is not so much more expensive, and has a much more powerful CPU (and GPU). Not really appropriate for a server use (idle power is too high) but for a desktop usage it’s still unmatched in value proposition in the sub-300 usd range.

Since the pricing is very volatile these days, I would recommend anyone to check how the pricing has evolved in case you read this review later in the year.