How I Built My New Linux Gaming Desktop In 2021 With Amd Cpugpu And Gnu Guix

After my unexpected luck in getting a new GPU (the AMD 6700XT), it was finally time to build a new computer. While my previous desktop was still ticking, at 6 and a half years old (an Intel i5-4690K, Nvidia GTX 970; see details in our gaming rigs article) it was certainly not up to 4K gaming and VR. The GPU was by far the hardest thing to get, but by this summer most everything else was available and at more regular prices.

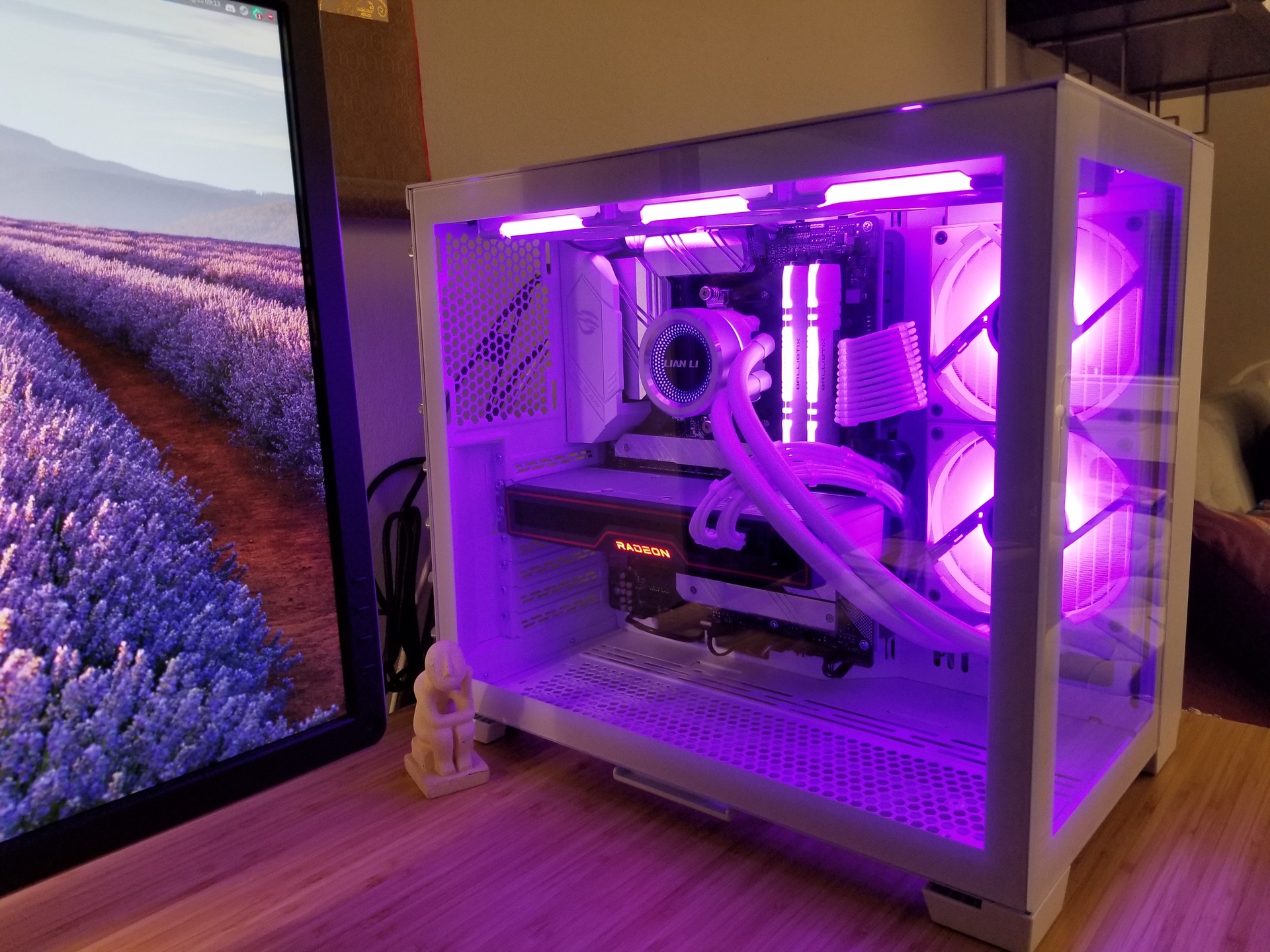

So what does a Linux gamer build in 2021? And does it mean I’m having an (early, I hope) mid-life crisis if I desperately wanted glass and lots of RGB lights?

Let’s find out!

The Specs

First, here’s the build I decided on, and am happily typing this from:

- CPU: AMD Ryzen 5 5600X 3.7/4.6 GHz base/boost clock with 6 cores, 12 threads

- GPU: AMD 6700XT with 12 GB memory (reference model)

- Motherboard: Asus ROG STRIX B550-A Gaming with PCIe 4.0 support

- RAM: 2x8 GB DDR4-3600 CL16 Crucial Ballistix RGB (white)

- Storage: Mushkin Pilot-E 1 TB M.2 NVME

- Case: Lian Li O11 Dynamic Mini (Snow White edition)

- Power Supply: Corsair SF750 (fully modular, 750 W, 80 Plus Platinum)

- Cpu Cooler: Lian Li Galahad 240 AIO (240 mm all-in-one closed loop liquid cooler)

- Case Fans: Lian Li Uni Fan SL120 (x3) and AL120 (x4) white RGB fans with controllers

- OS: GNU Guix

- Total: Approximately $1,800 (from various retailers, not including some tax)

Overall, the main components follow a pretty typical mid-range to enthusiast gaming build for 2021. These are all solid, well recommended choices, at a good price to performance ratio. I’ll discuss my choice to move to all AMD below, but overall there wasn’t anything I had to worry about being Linux compatible. These days I’d mostly be concerned about Wi-Fi, along with any specialty hardware. I opted out of Wi-Fi since my desktop is right next to my router for a wired connection, though the Bluetooth would be handy for things like controlling the Valve Index’s base stations. That and Wi-Fi can be handled with a cheap USB adapter if I want it. (Honestly, the motherboard I wanted in white also didn’t have Wi-Fi, so that made the choice easier, too.) The only thing for me was wondering about controlling all that RGB, but open source comes through again, as I’ll detail later.

In terms of specifics the 5600X is a great performer with the latest Zen 3 architecture and good single core performance to go with the 6 cores and 12 threads. This has become easily available, at least in the US, at or below MSRP. There are some great Zen 2 CPUs to pick from, but in my case I wanted the latest (I tend not to upgrade frequently, obviously) as well as plenty of power for photo editing and compiling as I’ve been contributing patches and packages to Guix.

I’ve had Asus motherboards before and have been happy with them, and their line of the B550 chipset comes highly recommended (often the B550-F Gaming with or without Wi-Fi). The features are close to the higher end X570, including one PCIe Gen4 for the latest fast storage, if you want it. M.2 NVMEs are pretty affordable, and I went for the Mushkin as one with good performance and price (there are lots to choose from), though only Gen3. I felt 1 TB would be a good amount of storage for my photos, several big games, and files, based on my previous build mainly using a 500 GB SSD. I may add another M.2 later, or move some of the several SSDs I have in the old desktop over.

Finally, I decided on a white color scheme with water cooling for the CPU, along with plenty of RGB, that I’ll also go into more detail below. Now, LEDs everywhere is purely an aesthetic choice, but having long wanted a nice looking case with glass panels, it would be good to have something to look at. And, I figured, it would be fun to see what I could do with the lights on the software side. The Lian Li Uni Fans are awesome in that they allow you to slide fans together to connect them and run just one set of cables for a whole cluster (up to 4), rather than cables from every fan for the lights and fan. The set of 3 fans also comes with a controller, letting you further run 4 total clusters (16 fans) with only needing one set of cables to connect to the motherboard.

I instantly liked the O11 Dynamic case series from Lian Li. I’ve admired Lian Li cases for a long time, as they always seemed well built and beautiful, back from when I built my first computers and there wasn’t much between the beige box and “gamer aesthetic.” While I’m generally a fan of black everything, when I saw the new white version I had to have it. So the “Snow Edition” was what I got, luckily just coming into stock when I was shopping. I should note that the O11 Dynamic Mini case is sort of a large mini-ITX or small-ish ATX case, that requires an SFX or SFX-L form factor power supply (unfortunately more expensive for a good one).

Water cooling is something I’ve been interested in before, but back when it was new and still a bit haphazard. These days you can get high quality all-in-one (AIO) closed loop, meaning everything is sealed and ready to go, liquid CPU coolers at different sizes, colors, and looks, for reasonable prices. They work by transferring heat from a metal plate on the CPU to water that is circulating past, on to a radiator made of lots of small tubes to dissipate heat, as fans also blow air across it to cool the water before it returns to the CPU. Liquid coolers tend to be quieter (lower speed fans on the radiator) and more efficient than air cooling. I chose the Galahad as a good performing (in terms of temperature and noise), moderately priced, and well reviewed AIO that had lights and came in white.

If you really want to drool over keeping your computer cool, check out the custom loops people make: hand cutting and forming the tubes, replacing the heatsink and fans on a GPU with a water block, adding a reservoir of liquid, and of course testing for many hours for leaks. But the end results are stunning, just search Reddit or YouTube for custom loops people have made and guides on how to make your own.

In the end, this is my first build with: windows (the physical kind!), lights, a Lian Li case, and water cooling, fulfilling a teenage dream. (Okay, also a 20s dream. And current one.)

Plenty of boxes and that new electronics smell to enjoy! With parts I wasn’t familiar with and the extra cable routing due to the fans and RGB connections, it took me longer than normal to get it all built. But after part of an evening and the next morning everything was in place, nicely cable routed, clean, and ready to rock. I’m very happy with how the final aesthetic and performance turned out. And yes, I’m still captivated by those LEDs!

Why AMD?

A question that has come up recently, in both our surveys and when I have written about my hardware, is the old Nvidia/Intel vs AMD debate. While I could note that all the recent security issues have had (at least slightly) more impact on Intel, or the potential performance gains from an all AMD system, really it came down to two things for me in the switch. One is AMD’s more open (but not completely! see below) approach to their GPU drivers compared to Nvidia, and the second is that I just wanted to try something new (especially after suffering through Nvidia on my laptop). While there are open source drivers for Nvidia, nouveau, it can’t replace the proprietary official Nvidia drivers for modern gaming. For AMD the situation is reversed, as Mesa’s open source AMD driver amdgpu is at least as good as AMD’s closed source driver.

Really, that’s about it. Nothing too insightful, I know, but I’m not alone among the Linux gaming clan. AMD has made huge leaps to catch up and outperform Intel, and at least compete with Nvidia this (unobtainable) generation. AMD’s spearheading of more open software and standards, like FreeSync and now FSR for any manufacturer to use, just fits better with why I run Linux in the first place. Throw in good, if not as affordable as previous generation, pricing, and I’m sold.

There were a few minor bits to learn along the way, as when I moved from my Nvidia 970 to the 6700XT. On the motherboard and CPU side, one was not finding the automatic optimized RAM configuration in the BIOS. Looking for XMP (Extreme Memory Profile) left me scratching my head, until I learned that it is Intel specific. For AMD I had to enable DOCP (Direct Over Clock Profile).

Hardware Choices and Openness

One question that I’ve become more aware of lately is: how open is hardware? While so much now “just works” on Linux, beneath the surface there is more going on. My prime example here is my AMD GPU. The drivers I use are open source, from Mesa, as I discussed previously. However, that’s not the only thing you need to fully utilize that expensive new hunk of metal. There is also a binary blob that the kernel needs to load (think firmware) in order to really use the GPU.

The distro I’ve started using on this new desktop is GNU Guix, a relatively new source based distribution with substitutes (pre-built binaries) built on the Guile Scheme language (that runs Shepherd rather than systemd). That “GNU” is standing for a lot. In particular, this means that Guix only officially supports open hardware with the Linux-libre kernel, following the Free System Distribution Guidelines (GNU FSDG). That means the kernel cannot contain or load binary blobs, proprietary firmware, non-free licenses, obfuscated code…no funny business. The end result is that some hardware will not work or be supported, typically things like WiFi or…some GPUs.

I could boot the Guix installer on the new system, after specifying the nomodeset boot parameter for the kernel. Basically everything worked, the only exception being that the display output was limited to 1024x768. It is possible this would be improved once I had the system setup (and newer Mesa version?), but without the AMD firmware that 6700XT wouldn’t be doing very much at all.

I note this for two reasons. The first is to highlight how open source may have hidden, less-than-open parts in practice, like graphics drivers. The second is on a positive side: everything worked without proprietary junk!

Of course, to do what I wanted with this machine I would need the full Linux kernel to load the non-open blobs (this includes CPU microcode updates, which is used to fix CPU bugs and security issues). But other than the GPU, everything works without it. And on the software side, only games and Steam pollute my otherwise FSF compliant system. These are all isolated via Flatpak in my current setup. Let’s not forget freedom 0: “The freedom to run the program as you wish, for any purpose.” So while the FSF will not endorse or support things like a binary kernel blob (like AMD) or drivers (like Nvidia) for full utilization of many GPUs, they won’t stop you from doing that on your own system, even on their own distribution.

Speaking of software, I mentioned above wondering if I would be able to do much with all those shiny LEDs in the fans, water cooler, and yes, even the RAM. Turns out this is related to a problem in Windows-land, as every manufacturer has their own (proprietary, of course) software solution they want you to use to control just their own LEDs. Mixing and matching hardware means even more software.

The solution to that and using these things in Linux is the open source, GUI and SDK, OpenRGB. This works across many different pieces of hardware to bring them under unified control. I can verify it works well in Linux, though I haven’t done anything fancy in it yet, other than setting the same color everywhere. Unfortunately, when I later added the newer Lian Li AL120 fans, that controller isn’t (yet) supported by OpenRGB. I might give a go at adding it in, but haven’t had a chance yet.

(Side note: I wrote a quick package to get OpenRGB for Guix, which I should submit. I also reverted a commit that makes OpenRGB not detect both of my RAM sticks. Good ol’ open source.)

I’d also like to write some scripts that talk to OpenRGB to control the lighting based on events like the temperature, a notification or game state, or reacting to music maybe. The inside of my new computer already looks like some futuristic night club, so why not go with it?

Final thoughts

I must say it has been a wonderful jump going from a 6 year old machine to 2021. One thing that stood out to me was comparing the processors: I went from an Intel Core i5-4690K with 4 cores and threads and a clock at 3.5-3.9 GHz, to the AMD Ryzen 5 5600X with 6 cores, 12 threads, and a clock speed of 3.7-4.6 GHz. And at each single thread cycle at least 25% more instructions executed (IPC). Twelve threads! That’s a nice full htop to look at. I haven’t benchmarked much, but a quick run with the Phoronix Test Suite’s kernel compile time test came in at about 107 seconds.

It was also a pleasure working in a modern case, there everything gets routed underneath the motherboard and out of sight, with plenty of routing options, tie-offs, and a nearly tool-less design. The Lian Li O11 Dynamic Mini is a really well thought out case. It is a long way from the SFF shoebox cases I worked on 15 years ago.

Everything is nice and quiet, basically just the sound of the case fans at low speed, which is also important to me with the new case sitting on my desk (to gawk at). I can verify by looking that the GPU fans are off for normal desktop usage, and the power supply also remains passively cooled at low loads. My previous case was built to be quiet, but all that sound dampening also lead to poor thermals. I really should have added fans. As you can see, I didn’t skimp this time.

I should add, it is quiet and cool. Right now sitting in a warm 3rd floor room, the CPU is idling around 36 C, or around the low 40s if doing a little more. (My previous desktop idled in the mid 40s.) This is with the water pump at around 60% and all the fans pretty low. Liquid coolers tend to run more efficiently than air cooling and I have the BIOS settings to only ramp up fans when the CPU hits 60 C (still tweaking this). The Galahad cooler can have some more audible pump whine at higher speeds, but with it only hitting that when the CPU is pushed hard, I haven’t noticed it with the other fans going too (or with headphones on).

Finally, let me end with some quick words about GNU Guix. As a big Lisp lover, I knew I had to try Guix when I saw it was built on Guile (an implementation of Scheme, which is a minimalist programming language in the Lisp family). Then I saw the features, including: a system configuration in one readable file, roll-backs of both packages installed and system configuration, mix and match versions of anything, easy package transformations (like updating to the latest version before the package is even updated or changing the git branch), and more. In short, it is a new way of making a distro (nixOS is similar in many ways, too). If you are curious, you can also install Guix as a package manager on any other distro.

There’s a lot more to say, which I’ll be writing up in some future articles to introduce everyone to Guix and breaking out of GNU-land for a gaming machine. (Note: please don’t discuss non-free software on any official Guix channels, like their mailing lists or IRC channel. They are friendly and will just politely remind you, but best to discuss somewhere like #nonguix on IRC.)

For right now I can say that I quickly got everything running the way I like it and have been thoroughly enjoying writing new packages, submitting patches, and interacting with a very friendly community. The most important bits for a gaming build is having the full Linux kernel and available firmware, through a channel (aka repository) known as Nonguix, as well as installing Steam (available in Nonguix, but probably best through a Flatpak beta right now, which also provides more current Mesa drivers). It is certainly a learning experience, and not for everyone, but I’ve found a new obsession and love for the Linux world. From early AMD 64-bit processors and living on the cutting edge of multilib on Debian, to Gentoo on a media server, seems like I’m always looking for my computer to also be a learning project.

I can say that ease of getting set up from real experience. After setting an ext4 option, large_dir, I learned that GRUB does not play with new (err…4 year old) features of ext4. I like ext for its maturity and performance, but I was undone by GRUB. I ended up doing a reinstall (this time with Btrfs!), but with my system configuration in a file, all my package choices in other files, and my dot files repository, I was up and running in just a few commands.

I’m still putting the new system through its paces and will detail my software setup in future articles, but so far so good. I don’t have any head to head benchmarks with the previous build and the 6700XT, but even on something like VR, which will be GPU limited in general, I was clearly held back by my CPU and other components. Now I’m enjoying super sampling (higher resolution rendering) at a smooth 90 (or 120!) Hz in VR and some Red Dead Redemption 2 cranked up at 4K, too.

Anyway, time to get back to VR, Half-Life: Alyx, and staring at those nice LEDs through the glass sides.