The State of Virtual Reality on Linux Gaming

When I first learned about that virtual reality stuff, I was still a kid and it was through movies like The Lawnmower Man. I really did not understand what it was about: it was very confusing, some people in a place doing things… but they weren’t in that place, and those things were not real. Later, in the 90’s when I was in college I actually understood the concept and saw news about some consumer products (but never saw them in person). I also met Linux in that decade and by the end of it, I was already using Linux exclusively. These expensive excentricities got out of my mind.

…Until after some life changes, an unexpected influx of money, and curious about all the news about Half-Life next installment (Alyx) and Valve’s own VR system, the Valve Index, and the claims that it is supported on Linux, I took the plunge and bought it. I got it on my house on April 30, 2020, an exact year after its debut.

What happened to me next was extraordinary. I met new worlds, I felt new things, I traveled to many places in the hardest months of the Lockdowns. It is not easy to describe, since it is so linked to the senses, so real and at the same time so abstract. In this article, I’ll try to laboriously describe what I felt – without ever leaving Linux – and give numerous examples. For that, though, I have to start with boring stuff. Stay with me and you won’t regret.

So. This article will try to convey how Virtual Reality on Linux became viable, what are its challenges and limitations, which applications and games run on it, what are the terms and technologies associated to it and what to expect from the future. And also give a light whether it’s worth investing on this technology today, instead of waiting for it to mature as most people must think.

A Small Disclaimer

The technology and devices presented here are not only expensive but sometimes impractical to acquire in some regions. As an example, while I live now in Europe, in my home country of Brazil the Valve Index is not officially sold by Valve and the very few stores who sell it charge at least thrice the price. So, this is currently a non-inclusive technology much like the region-locked Stadia or GeForce Now, which might seem distressing to some and contrary to the spirit of availability of open source. In that case, please regard the following text as a prospect for the future, since I believe the technology will get much cheaper and arrive to the masses, everywhere.

A Short History of Consumer Gaming VR

Virtual Reality, or VR as it is commonly known, is the computer-generated simulation of a three-dimensional environment that can be interacted with by using special equipment that gives a realistic and physical way to do it, like enclosed glasses with screens instead of lenses, and clothing with pressure nodes that simulates touch. Related to VR, there is Augmented Reality, or AR, which is a interactive experience in a real-world environment where the objects in the real world are enhanced by computer-generated perceptual information in their perception; for example, adding the visualization of 3D models in the real room you are in. In practice, today, AR’s technology is already integrated into VR, so, for example, virtually all current-generation headsets have cameras which might be used to generated the backgrounds for the virtual scenes you are seeing in their screens.

VR has gone a long way since its inception in research laboratories in the 80’s (with early research going back to the 60’s), and with the first consumer electronics in the 90’s, it always seemed a niche technology that had it right around the corner to become popular, but never did.

In 2012, after more than a decade of VR being out of the public eye, and after a successful Kickstarter campaign, the first modern VR headset, the Oculus Rift, debuted. It was not a kit with its own motion controllers at the time, that would come later; it came with a Xbox One controller. The wired headset was possible due to the convergence of many technologies, specially the miniaturization and commoditization of MEMS sensors (used for gyroscopes, accelerometers, position detectors) and the advancements in portable displays. The headset gained adoption slowly with a few titles supporting its proprietary API.

Other companies started researching VR, with Google notably attempting to popularize VR technologies with its “Google Cardboard” initiative in 2014, a low-cost stereoscopic viewer (two ‘screens’, one for each eye) to be used with VR-enabled applications running on a cell phone screen. In that same year, Valve debuted its SteamVR technology for the Oculus Rift.

In 2015, a competitor, the HTC Vive, launched, with its own motion controllers and SteamVR support, and Oculus followed suit in 2016 with the “Oculus Touch Controllers”. The Playstation VR headset also launched that year, allowing its use with the 2010 Playstation Move controllers. 2018 saw the appearance of the first standalone headset, the Oculus Go.

In April 30, 2019, we have the appearance of the Valve Index, the very first VR kit to officially support Linux, and at the time of this writing, the only one to do so. All the other VR devices that work, do that either through SteamVR or through rough reverse-engineered drivers.

You’re right, that was boring. Besides, why is VR even relevant and not a fad?

Yes, that was boring, but did you notice that small detail? The motion controllers of the PSVR were created in 2010, years before any of the headsets. And suddenly, they perfectly matched the PSVR. Also, they are just the latest on a long history of similar spatial controls – the Wii remotes and even the Xbox Kinect camera have a bearing on it. This is the output that provides physicality to VR.

The headset and the controls perfectly complement each other. Remember that dancing game on your Xbox in front of the camera? Well, it was convincing, but once you turned your head to the side you couldn’t see that big TV anymore, and that was even worse for first-person combat games (melee or shooters). It was a big downside in an otherwise exciting technology.

The same thing could be said of the stereoscopic vision: even with precise and fast head tracking, you get to be immersed in a virtual world only to see your “hands” be controlled by small, constricted movements with a joystick or mouse and keyboard combination, many of them not even resembling what you were doing in that virtual world.

Now it’s the time to mention that just like the controllers, the headset position also should be tracked to feel legitimate. When you only have the rotational awareness of the headset, that is, you only know to where it is pointing, this is called 3DOF, for three degrees of freedom, which are the rotational axes pitch, yaw and roll. When you also have position tracking you have 6DOF, with the additional translational axes X, Y and Z, and this position is usually relative to a device called a “base” or “lighthouse”, and you can have several of them. Google Cardboard “VR” only has 3DOF.

Many people only know “VR” through Google Cardboard because of the low price, and they deservedly think it’s just a gimmick, novelty or curiosity. They never get to feel the physicality,

And that’s not the whole story. There are still two more important points to consider. The first is that our eyes are very different from flat camera sensors. They are almost spherical and they have much sharper vision in the fovea (central region) than peripheral regions, so some adjustments to the image that appears so close to the eye is needed. Part of this is done with a form of supersampling, which you might know from game settings: the scene is rendered in a higher resolution than the physical resolution and then scaled down, usually with some form of aliasing to smooth corners. That creates a noticeable increase of image quality when using a headset. The other part of the adjustment is done with distortion and perspective correction for the approximately round field of view.

The cost of this is not cheap, though. For the Valve Index, which has two 1440x1600 LCD panels for each eye, the default “resolution” setting is 130%, which means two scenes, each with 1872x2080 resolution, to be rendered and then rescaled and distorted to account for one single frame.

That would not even be so bad for the second point: in VR, our eyes are much more sensitive to frame rate and latency than in a screen. When you move your head and there is even a slight delay in the information you see on the headset, the more basic areas of your brain interpret it as some kind of sickness and might make you feel dizzy, nauseous and even activate your gag reflex (to get rid of poisonous food). This is a real issue that might get milder with use, but it is also a blocker for some people and might cause health problems. So there’s no room for low-spec gaming, and while a 60 Hz monitor is great for most people, for VR you do not want to stay below 90 fps. For the Valve Index the default frequency is 120Hz and can be overclocked to 144Hz. Besides framerate, that’s also why wireless headsets are still quite experimental – latency is a big problem with those and you will need at least “Wifi 6” (802.11 ax with 9.6 Gbps and much better latency handling, used by the Oculus Quest 2).

What about Linux?

I will be frank here, I don’t think VR on Linux would be a thing… If it were not for Valve. While I understand that there are people who abhor DRM and will not get even close to Steam, if you want VR, currently there’s almost nothing – drivers and applications included – outside of Valve’s client. Consider that we Linux users are a tiny slice of the desktop market. Let us be optimistic and say that we are 2% of desktop users (although in Steam it fluctuates around 0.86%). VR users in Steam are around 1.9% according to the latest hardware surveys, and those are gamers, they are not representative of the desktop users, but nevertheless let’s suppose that 2% of desktop users have some kind of VR device. If the proportions hold, Linux VR users would be 2 percent of 2 percent, or 0.04% of PC users, or 4 people in 10,000, and scattered all around the world. That tiny market would not even be a consideration for any sane investor.

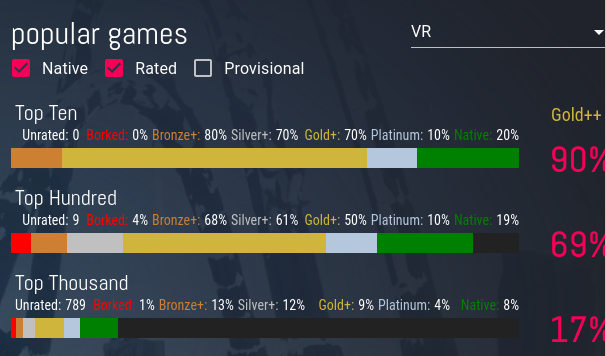

But then again, we have a few native VR Linux games, and more coming every day. Serious Sam games, The Talos Principle VR, Half-Life: Alyx, Groove Gunner, ASTROKILL, Allspace and a couple others. Granted, most VR-capable games with Linux builds do not even have VR on their Linux binaries, but some do, even with very janky and no support, like Everspace. And for Proton-based games that might sound surprising, but the likelihood of a VR-supported or VR-only game to work on Linux is greater than for a non-VR game. Which, by the way, might be referred as “pancake” games.

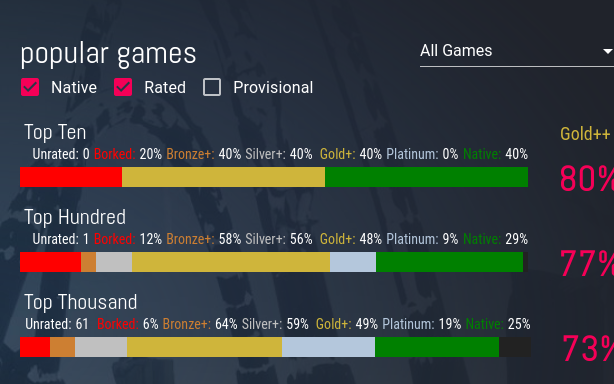

Protondb statistics show that. For all games:

Although they are less well-rounded than pancake games, VR games show a much lower likelihood of being borked:

Although they are less well-rounded than pancake games, VR games show a much lower likelihood of being borked:

Isn’t that surprising? That’s a merit of SteamVR which seamlessly work across platforms and Proton which integrates seamlessly with it. But it’s not all roses; there are some spines too. For all its sophistication, SteamVR has a few odd longstanding basic bugs on Linux, like the headset camera not working (although it is detected and viewed by popular camera software like Cheese and guvcviewer), the controller button combination for screenshots does not trigger (F12 works, but you can’t map it to the combination) and finally, the power management of the lighthouses (which can work via a small python script — and if you do not turn them off, they will spend all the time spinning and wearing off (see animation). If SteamVR was open-source, such bugs would be patched in no time, but for being proprietary and non-collaborative, we can only patiently wait for Valve to fix. There are of course some open-source mitigations for it like steamvr-utils which is added as a script when launching SteamVR to control the lighthouses and audio, but they are still peripheral instead of fixed in the core.

How a lighthouse works internally. Credit: reddit post. Check out this video animation of a room with lighthouses too.

How a lighthouse works internally. Credit: reddit post. Check out this video animation of a room with lighthouses too.

On the other hand, at the very same time SteamVR does sophisticated things that for all matters and purposes needn’t even be there. For example, extending your VR set with “vive trackers” — a device attachable to the body that informs where it is — is not only possible but easy and seamless, and you can easily play the games that support full-body tracking. You can also add additional lighthouses to the setup and SteamVR will detect them just fine.

There is also the case when it’s not even Valve to blame, but an external vendor like a GPU Maker. Podiki already explained in his own article, but let’s recall: Reprojection is a collection of techniques wherein if a scene frame is not ready at its expected timeslot for the screen frequency, a simplified version for the rotational and translational movements of the head is presented instead (the simplest form would just be shifting the rendered screen to account for head movement). Asynchronous reprojection prepares the simplified version simultaneous to the rendering and before the frametime is over, while the older interleaved reprojection runs the application at half framerate by duplicating frames.

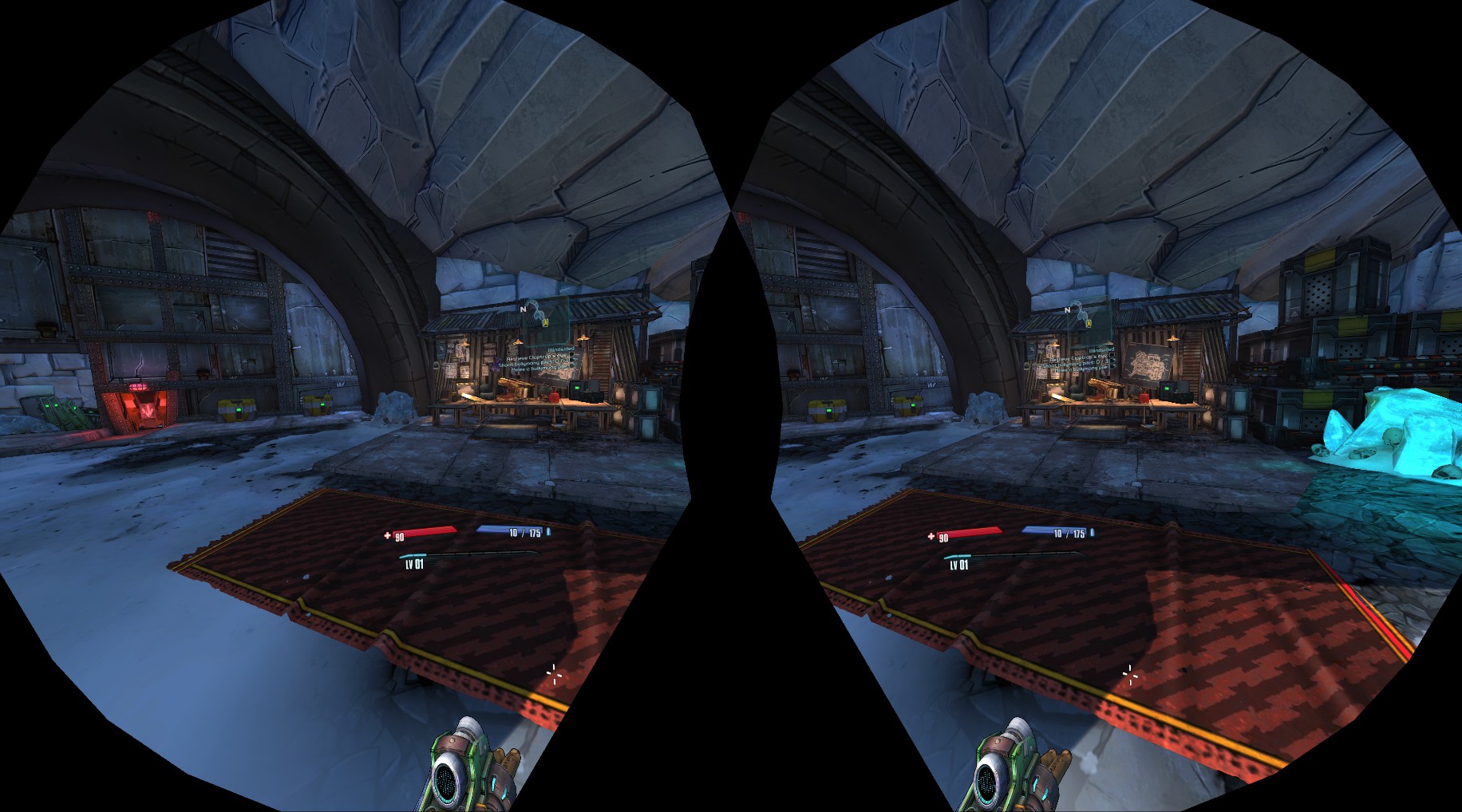

Reprojection is largely dependent on GPU and must be supported by GPU drivers. It might come to no surprise that current Linux NVIDIA drivers do not have asynchronous reprojection, while the open-source AMD GPU drivers do. That, by the way, is the main reason why Valve recommends AMD GPUs for Half-Life: Alyx on Linux instead of NVIDIA. As a previous owner of an RTX 2070 SUPER, now owner of a Radeon RX 6800 XT, I can say that AMD feels much better for VR – including the fact that some games which did not work for me under NVIDIA now work with the Radeon, Portal Stories: VR and Borderlands 2 VR being examples. This does not mean it will not work for you, I have friends with NVIDIA GPUs which report to me that these games work correctly on their rig.

It is of note, though, that if the game has good performance and frame drops rarely happen, reprojection isn’t much of an issue. On SteamVR, the type of reprojection to use might be configured on a case-by-case basis (for each game), and NVIDIA users have to laboriously change many of its games to “legacy” reprojection to ameliorate the unpleasant effects of framedrops.

Windows users have asynchronous reprojection on their NVIDIA drivers, so they don’t need to fall back to legacy reprojection. Their experience is thus less disorienting. There were attempts to ask Nvidia for the feature, but got no response from them.

So, how is it to use VR on Linux?

If you use the officially supported Valve Index kit or the SteamVR supported HTC Vive or Vive Pro, your experience should be seamless. For other headsets which might not have all features or have some sparsely found reverse engineered drivers — like the PSVR or the Oculus Rift DK1, in practice you won’t be able to use it for games or serious applications: the drivers do not serve the right APIs and the VR set (controls, lighthouses, head-mounted display, etc.) do not work as a whole. They will be nerdy devices for tinkering and unfortunately seldom have practical use.

SteamVR officially started in 2015, when Valve created the OpenVR API for multiple vendor support for VR devices. Although most parts of the SDK are open source under a BSD-3 Clause license, the drivers themselves aren’t. So, a few early adopters of the technology started developing an alternative implementation of OpenVR called “Open Source Virtual Reality (OSVR) which even had open-source hardware projects. Sadly, its development stalled and even today its main site is offline.

But in the end, it seemed better this way, because the semi-closed OpenVR gave way to OpenXR, a Khronos Group-led VR API which debuted on July 29th 2019. If you don’t recall the name, Khronos Group is the commitee responsible for OpenGL and especially Vulkan, the graphics API that has been so crucial to linux gaming success lately. OpenXR is royalty free, fairly well documented, synchronized with Vulkan, supported by browsers and multiple vendors. SteamVR beta already supports OpenXR (besides its native OpenVR), as does the Windows VR standard [Windows Mixed Reality(https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/mixed-reality/windows-mixed-reality). Even the Oculus PC platform supports it, so maybe it will serve as a bridge for the proprietary games/applications from these platforms to some day work on Linux.

Being open that way, OpenXR allows for competing implementations, and besides SteamVR we have a multiplatform implementation called Monado which, different from OSVR, seems to be progressing quickly, supports more modern devices, and already has applications built on top of it, one of which is XRDesktop, a library for taking traditional desktop interfaces to VR. There are other initiatives in the field or VR/AR interfaces, like Arcan with the SafeSpaces Desktop, but this will be a separate article for the future. For the moment, you might want to see the splendid explanation from Collabora on how XRDesktop works.

Monado is only the OpenXR implementation, though. Not the low-level drivers, which recognize and drive the joysticks, head-mounted display, trackers and the likes plugged to your PC. For these, outside SteamVR, there is an open-source project called OpenHMD. Still seems on its infancy, though, with Positional tracking only supported for the japanese tracker NOLO at this moment.

On Linux, in practice, to use VR (after you plugged in all devices) you’ll go through Steam and install the SteamVR tool. Then to use anything in VR, you’ll have a number of ways:

- You can click PLAY on the SteamVR application. It will start SteamVR (at which time your HMD will turn on and a simple infinite landscape will appear on it and respond to your head movements) and by default it also loads SteamVR Home, a 3D environment interface where you can walk, interact with objects, change settings and launch games and applications which are VR supported. Some applications which are not officially VR supported might not appear on its launcher widget, forcing you to launch via the pancake steam window. You can also change the 3D environments (there’s Workshop support) and even meet your friends there, with voice chat and all.

- On some distros like Ubuntu which are very integrated to Steam, when you turn on the controllers it automatically launches SteamVR. Note that since the controllers use a proprietary driver, they do not appear as regular Linux devices like the ones in the command

xinput list, so there is no chance of customization outside Steam. - In the corner of the Steam window, next to the “big picture” widget, a “VR” widget will appear. If you press this widget it will also call SteamVR.

- Calling a game that has VR support via the “Play” button on Steam. If it is a SteamVR game which is “VR supported” as opposed to “VR only”, it will ask if you want VR mode. Steam automatically adds the parameters

-HmdEnable 1to the game command invocation if so. This way, the game will communicate with the SteamVR dynamic library and start in the headset screens. The timing here is not always perfect and as an incipient technology, it might fail at times, but this has been steadily improving. Also, there are a few games and applications (e.g. Blender, City Car Driving) which start in normal desktop mode but have a “VR toggle” control inside them that will switch the display to the headset.

Note that besides SteamVR Home you also have a 3D VR overlay that you can call by clicking the “system” button on the haptic controllers. This overlay is like the SteamVR window that appears on your desktop but more configurable and even allows you a “virtual desktop” mode to control your desktop like XRDesktop. This is where to configure per-game settings, specially important settings like motion smoothing and reprojection. At the time of this writing, the overlay still has some weird intermittent bugs: it sometimes fails to load correctly and works poorly (e.g. no virtual desktop) or not at all. And it sometimes has a huge latency on some dialogs.

SteamVR takes control of the VR display, and apparently there is no way to intercept SteamVR Home or the overlay for screenshots on Linux. So you have to use SteamVR’s own option to have a mirror of one eye on the screen (some games like Half-Life: Alyx also have this as a separate, in-game option). This is the way you would record or steam a VR game, and due to the lack of direct access it’s heavier for Linux users – e.g., the OpenVR plugin for OBS Studio which allows it to record directly from the headset only works in Windows.

The SteamVR setup

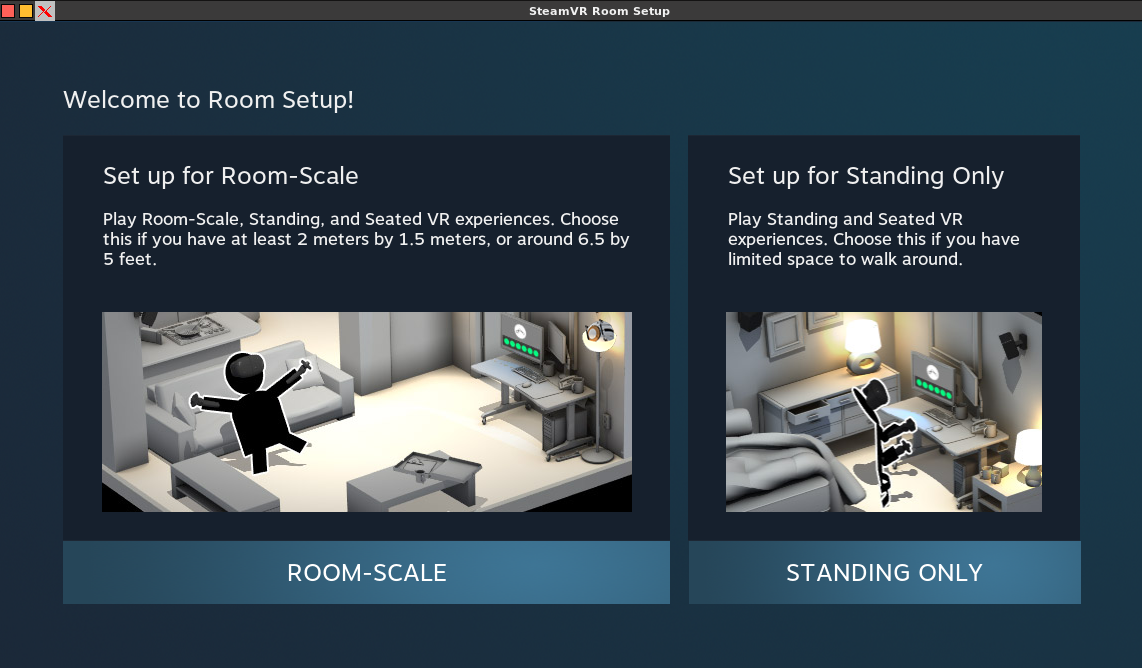

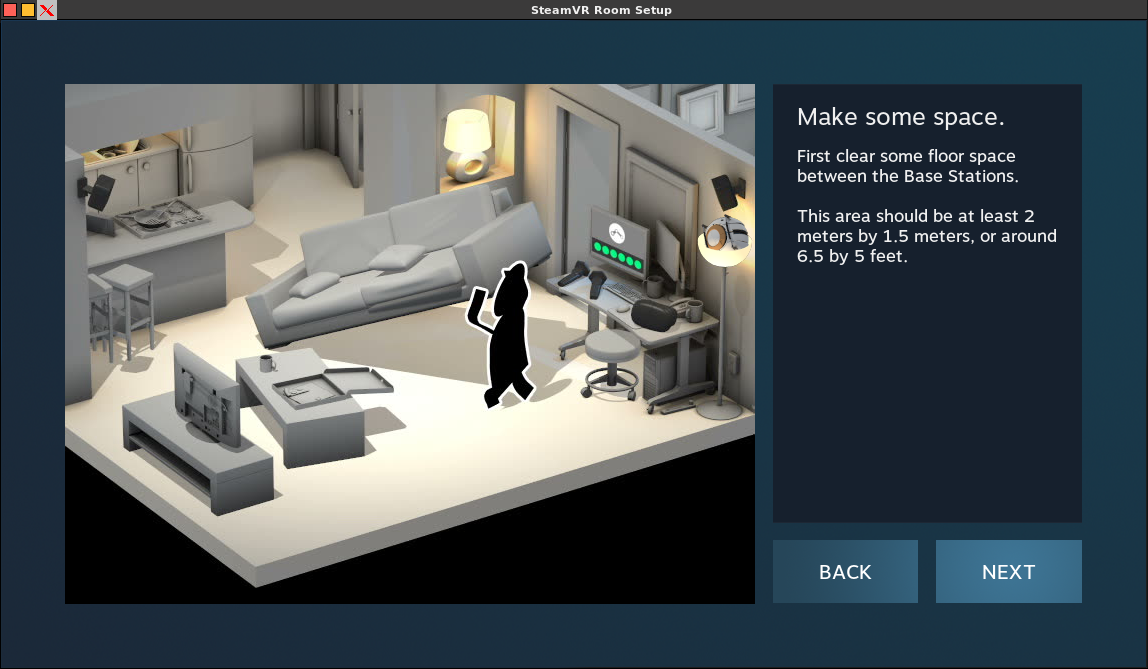

Besides starting SteamVR, after you plug your VR kit there is a simple calibration procedure to tell SteamVR how you prefer to play your games. Broadly speaking, VR games and applications in general are operated in one of three different ways:

- The Seated experience. This is very much like the way you already use your PC, seated in a chair usually in front of your desk. This is the most limited use of VR and unfortunately the most frequent way people internalize it. In this mode, you will usually not use the positional axes of the headset and controllers much and VR add-ons like body trackers make little sense. It is preferred by VR desktop applications and VR games which do not use VR controllers (including those that might use specialized controllers, like Elite: Dangerous with HOTAS or Euro Truck Simulator 2 with a wheel).

- The Standing (or standing only) experience. This is used when you are in a confined space but need to use VR effectively with its controllers, including the positional awareness. This is not often said, but when you choose this mode it usually also implies that you would not be physically turning around more than 180°.

- The Room-Scale experience. This is the broadest VR experience on Steam (the broadest possible would be with standalone / mobile headsets, which allow you to roam around even in open spaces). It has a minimum mapped space requirement and it is also the mode of choice for more physical games, specially the ones which require you to perform real turns… which might get awkward with cables, and there are even add-ons for counting the number of turns so that you can quickly unturn that amount and unwind your cable.

SteamVR requires you to choose between “standing only” (which includes seated) and “room-scale” experience. The choice you do here is also linked to the way you position your lighthouses to optimally detect your movements. It is of note that although you can play with as little as just one lighthouse, two are preferred for most cases and if you plan to do lots of turns or have several trackers on your body, even three or four might be advisable for best detection. The detection and use of lighthouses is automatic, so you can also buy more later.

As a safety measure, the SteamVR API uses the grid you traced with your controls in the calibration process as the boundaries of allowed movements. In any game, in SteamVR, or in the empty landscape, if you get within 70cm (2.3 feet) of these boundaries, an increasingly bright neon grid appears. This grid is called the “chaperone”.

How immersion worked for me

As I knew I was getting a relatively novelty device when I purchased my Valve Index, I took notes for weeks and even sporadically during months to record my progress with the technology, matching the impressions I had with the hours recorded on SteamVR. Of course, these are mostly subjective and as any other human, I am full of biases, so take these with a grain of salt. However, as I also discussed my experience with many other persons using VR, I am confident that the it might be typical enough to be reported.

First thing to note is the “nausea”. You might be familiar that, at least for the first times, almost everyone feels uncomfortable using VR for a couple hours or more. While it is referred as “motion sickness” as a general term, I found myself feeling three distinct effects:

- Retching: That is that involuntary movement of the stomach (retropersistalsis) when you choke or eat something poisonous, and in my case I am also referring to the feeling that it’s coming. This is the worst effect and the one that limited my VR sessions the most. I stopped feeling this after SteamVR clocked 400h.

- Disorientation/dizziness/vertigo: while they are not exactly the same thing — dizziness is an altered sense of spatial orientation, while vertigo is the sensation of movement of your surroundings — they feel very alike. It is not as crippling as the former, where it impacts most is your sense of balance and coordination. By around 700h of VR use, this one stopped. It still comes back in a weak form when I try some new VR games with different controls.

- Headache: This is that feeling of pressure in the back of the head, and now (2500h+) happens only after very long sessions of highly demanding games. Since much more of your senses are used than a regular game, I attribute this one to high cognitive load and fatigue. I did not feel that much in the beginning because I could not engage in long VR sessions.

All these effects contributed against my feeling of being in a different place, not only by limiting time of exposition but also by blunting my senses during the VR use. Once I got rid of them, it was like adding color to a grey world: the immersion greatly increased with time.

As a note, all these effects are one way or another linked to low and unstable framerates; having a powerful CPU and GPU configuration from the start — or choosing lighter games — would make them milder and more bearable. There are also a number of methods that can ameliorate these symptoms. There is no definitive set, but the most common are:

- Vignette: this is a graphical technique used in photography and movies which makes the borders of the picture frame fade to black. This sort of mimics a squint of the eyes and by restricting the field of view, allows the spectator to concentrate on the center. In VR games, this is generally used with fast movement, like running or turning quickly. When the effects get more intense the faster you go, it’s called tunnel vision.

- Teleport: This is also a method of locomotion, that is, a way for the player to substitute not having “VR feet” like he has “VR hands”. The natural method would be to use the sticks in the controllers for smooth locomotion like in regular pancake games, but the dissonance with the vestibular system (which gives our sense of balance) creates the ill effects for new users. So the teleport technique consists of one using the controller to point to a spot in the ground which gets illuminated, and press a button or flick the joystick, and they are instantly teleported to that location (in some games accompanied by very fast fade-out/fade-in); this movement also substitutes jumps and ladder climbing. This is called blink teleport and users who get comfortable will eventually change to smooth teleport, which replaces the fade with a very quick slide to the target, maintaining the illusion of movement.

It is interesting to note that when doing smooth locomotion, the direction of the movement is usually to go to where you are pointing the joystick, but some games allow the option to be to the direction you are looking. The former allows you to look to the sides when moving forward and the latter allows you to run shooting enemies outside your field of view. A game with full-body tracking could use your belt tracker or feet trackers to determine the direction to which you are going, combining the advantages of the two techniques.

It is interesting to note that when doing smooth locomotion, the direction of the movement is usually to go to where you are pointing the joystick, but some games allow the option to be to the direction you are looking. The former allows you to look to the sides when moving forward and the latter allows you to run shooting enemies outside your field of view. A game with full-body tracking could use your belt tracker or feet trackers to determine the direction to which you are going, combining the advantages of the two techniques. - Snap Turn: just as sliding movement, rotating your body in VR might disorient, so turning is broken into discrete angles to which you immediately turn after a flick of the designated joystick (usually the right one). Again, fading usually is an option here. Note that a few games do not have the controls to turn, they require you to turn “for real” in order to change directions.

- Other Methods of Locomotion: while not necessarily linked to disorientation, VR game developers have much more room to experiment and risk than pancake game developers, and many creative methods of conveying motion have been invented. From quickly swinging your arms to pretend you’re running like in Sprint Vector, to point to a spot and fling to it like in Windlands 2, to use additional equipment with Vive sensors to “jog in place” like in The Path of Greatest Resistance. Some games like Star Shelter and the free Home - a VR Spacewalk to simulate you drifting in space make you grab handles and propel yourself in zero gravity, and a similar gameplay with a simulation of swimming can be seem in games like FREEDIVER. As you can see, because of the more organic controls, the possibilities are endless.

Besides the ill effects, I noticed very early on that the smart use of the positional haptic controllers makes a big difference in immersion. Without them, it is like being at the top of a mountain and looking at the landscape: you can admire, you can feel the distance between you and all the elements in the landscape, but you can’t touch them, you can’t properly interact. You can use the invisible mouse, joystick or keyboard, but that’s like operating a vehicle, feels constricted and distant. You are a ghost. Conversely, when you extend your arms and feel the haptic feedback of “touching” something, or when you can infer the position of something via the 3D sound, that makes you a part of the scene. It is possible, maybe even likely, that games start creating completely blind levels where you should react to haptic feedback, spatial sound and motion inference instead of visuals.

Curiously, the feeling of operating a vehicle might be exactly what is needed for immersion. In games like Elite: Dangerous — which allows the use of a HOTAS set (Hands On Throttle and Stick) — and Euro Truck Simulator — which allows the use of a force feedback wheel with gears and pedals —, the inability to use the haptic VR controllers is countered by these devices. But, again, do not doubt the creativity of VR game developers: movements that mimic both HOTAS (in VTOL VR, No Man’s Sky) and wheels and gears (Mini Motor Racing X, Thief Simulator VR) using the VR controllers has proven to be a valid option, specially in the case where you eventually leave the vehicle!

In the diversity of scheme tropes, one of the most annoying to my tastes is using the eyesight for output – like aiming by moving your head to get that enemy in the center of your field of view; this is prolific on games where the VR adaptation is an afterthought and it is related to mouse aiming, where it doesn’t feel odd. I fear that with the advent of eye-tracking/facial expression detection headsets, that might become even worse.

Full Body Tracking also enters the scene, with games that respond to movement from trackers where you are in a treadmill or even an exercise bike. One game of soccer, Final Soccer, besides letting you use trackers in a variety of ways, also allows you to use the controllers strapped to your feetso you can kick the ball! A dinosaur island survival game, Island 359, allows you to kill small dinosaurs by kicking them in the face! And, yes – these ludicrous ways to play work perfectly on Linux!

Getting physical

Whew, all these controller schemes look tiring, don’t they? And guess what — they are. A LOT. There is no lack of exercise games, which exercise not only the upper body but also in professional settings for training, like the boxing game Thrill of the Fight, all the while being a lot of fun. There is even a VR Health Institute which describes the physical effects and calory expenditure of each VR game!

But this exercising aspect, while initially confined to its own genre, has also been creeping and mixing into regular games. Until You Fall(*) is an exercise game with RPG mechanics that gets you tired very quickly. Karnage Chronicles is a much more complex action RPG which resembles Until You Fall in combat and you might leave a gameplay session quite exhausted. There is FREEDIVER: Triton Down, a story-driven diving game where you might get as tired as in a real swimming lesson. Even usually calmer games have this aspect: while some young men have been known to play the pancake game Starcraft 2 for dozens of hours straight, playing a similar VR RTS game like Skyworld would not be feasible for too long sessions without athlete grade fitness. Will we have the fat seated gamer stereotype shifted to an ultrafit individual? And there doesn’t seem to be an way out of it: older games like Skyrim VR show that clearly, in that the redundant stamina bar of the game works by skip registering hits when it’s low, which makes combat really awkward. Turning stamina off with a mod and using your actual body stamina makes the game more fun and immersive.

It’s not all roses, though. While for most VR games we would assume a standing position, this is a health hazard if done for long periods of time. While sitting down would be an option, it distracts from the game and might have an effect on it like restricting the freedom of movement and changing the avatar height. In some movies and public settings for VR you can often see some expensive tethering apparatus to hold the player like the Omni One, these are exceedingly expensive and difficult to acquire.

As for me, I chose a low technology solution that solves most of these problem: a swivel saddle stool. Gives me mobility to walk around my play area, allows freedom of upper body movement, stays at close to my natural height and gets my spine in a proper S position. It’s awkward for bending over and I have to leave it for crouching, but it mostly gets the job done. I can go through 5 or 6 h sessions with this setup, only doing a pause due to the discharge of the controller’s batteries.

It could be taller, but it works great for most long VR games.

It could be taller, but it works great for most long VR games.

Your mileage may vary, of course, and some people prefer to endure it standing, others prefer to just be seated which is possible in most games. Until the standing VR treadmills are affordable, we just improvise.

A Small Renaissance of Gaming

As you might have been inferring from the numerous examples I mentioned, I am quite infatuated with the variety and creativity of VR games. For a long time, people keep mentioning that due to the massification of the gaming industry the innovation and creativity have been declining, with developers sticking to safe known genres, mechanics and tropes to survive in a crowded competitive market.

While I disagree from the generalization (I see very creative indie games still being made, Tenderfoot Tactics being one recent example), I have to concede that the overall situation is much worse than ideal. Which leads us to the new game space of VR.

Do you remember when in school you were told that after the extinction of dinosaurs the mammals quickly irradiated in many species and quickly occupied the then-vacant roles of these dead lizards? The same can be said to VR games compared to pancake games. It’s not that pancake games are extinct, but VR games reside in something like a separate world, where they do not face direct competition with them. There is no Starcraft 2 VR, and even if it was adapted for VR, since it was not designed for it, it would probably be rather clumsy to play.

So for a games developer, creating a “killer game” in a genre in VR that everybody is compelled to play is much more achievable. Effectively using the VR visuals and controls is not standardized, which encourages wildly different, tentative approaches, specially after Half-Life: Alyx stablished the importance of physicality in-game. Since the success criteria is now different, even high production value titles like Star Wars: Squadrons (optional VR) and Medal of Honor: Above and Beyond (VR only) have not been able to distance themselves from the much cheaper indie titles. VR is on the rise, headset sales are so high that it’s one reason why shortages are frequent, so if you make a financially successful game now you’ll have even higher profits in the future due to the growing population.

So it pays a lot to be bold. So, you can’t move too far with your headset because your playspace is only 3x3m (~10x10 feet)? What about using non-Euclidean geometry tricks so that ou can actually walk a lot while staying in the same space, like in Spellbound Spire? Your space is even smaller, say 2mx2m (6.5x6.5 feet)? You can turn on amplification of steps, to have the effective 3mx3m space! You have a soccer game which could be played only with feet, but most people do not have the expensive vive trackers for full-body tracking? Well, let them configure their haptic controllers to be used as trackers and tie them to their feet in Final Soccer! You do not want the thumbstick turning the scenario because it is so immersion-breaking? Well, let the player grab the scenario and turn it with his hands as in SportsBarVR and many others. Do you think Retro Games would not have a place in VR? Think again, because with titles like 1976 - Back to Midway you have a chance not only to relive the arcades of old with a sense of perspective from above but also to switch for a first-person view and feel yourself in the middle of a real battle. 3DSen, a 3D NES emulator, has its own version in VR, and SEGA Mega Drive and Genesis Classics(*) has a virtual room in VR so you can feel the tactile sensations of dealing with physical console cartridges. I will not even mention the sort of craziness adult game developers have been coming up with – this is a “Safe For Work” portal after all –, but you might make your wild guesses.

Of course, these innovative elements are not conducive to success if there isn’t engaging gameplay, convincing visuals and other attributes. But that’s the hint – even failed games can indicate a good innovation which might be kept alive by more successful ones that copy the idea.

Besides new genres like exercise games, VR allows a whole new take on existing ones. The Invisible Hours is a mystery exposition game that feels much more lively in VR, due to the added freedom of movement you have. As so much of the gameplay in VR is linked to exposition, the same elements with now distinctive relevance make for a different experience. Also, the current representation of several genres in VR titles is not so bad, although with very diverse qualities. Do you feel the need to do naval battles like in Man O’ War: Corsair? There’s BattleWake for you. A good stealth game? Budget Cuts 2 or you might like Thief Simulator VR better. A Counter-Strike or Call of Duty-like game? Pavlov VR and Zero Caliber can work. Survival? Besides the already mentioned Island 359, The Forest has great VR support! And there is a version of Hellblade: Senua’s Sacrifice in VR, using over-the-shoulder third-person perspective. Want to clean houses? Why, House Flipper VR is there. Want a spacecraft-building space RPG/RTS mix? Space Pirates and Zombies 2 has an excellent VR implementation (via Proton)! Want to scratch the Minecraft itch? Well, it has a VR version, but you could also try cyubeVR that even promised a Linux build in the future (it currently works under Proton). Fancy some 3D social network with games and events? You can choose between VRChat and AltSpaceVR, both work under Proton, and you could also try the open-source Linux-native Vircadia (these social networks can also be played in the flatscreen). I could go on and on, but you get the idea!

In seems to me that this “bazaar” approach to game development is at its peak, and I even expect better ideas for control and interaction than the laboratory-centered approaches of interfaces like XRDesktop. Games cannot afford their interface to be clumsy or convoluted, it affects their commercial success a lot. It is amazing to see how some good interface tropes have already been growing, like a turnable, zoomable overworld interface for a 3D battlelike in BattleGroupsVR and Final Assault.

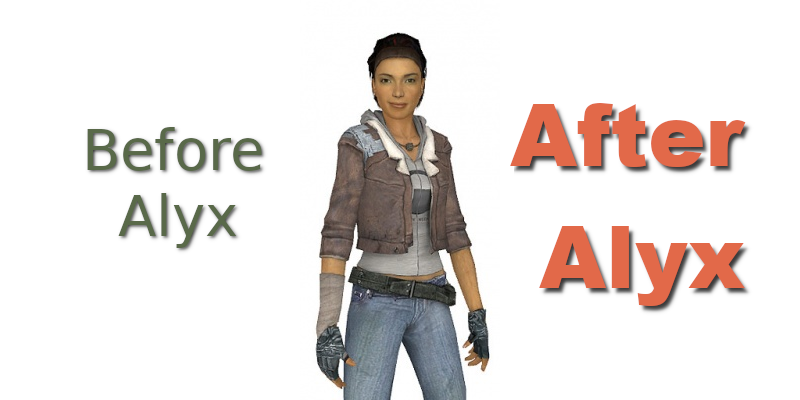

The Half-Life: Alyx era

With all the experiments and creativity going on in the virtual games space, one specific pattern is clearly distinguishable, and that’s the influence of Half-Life: Alyx. Kept in secrecy for a few years by Valve, its development was preceded by a massive internal amount of research and development in what works and what doesn’t work in VR, and a lot of new tropes now followed by game developers. Adam Savage’s Tested has a wonderful interview with Valve developers where they describe the creation process for the game, which helps understand how revolutionary it was. In the latest releases of Alyx Valve added optional developer commentary which shows hurdles and solutions to each game section.

And by saying “revolutionary” I am not doing a hyperbole. The game, besides being a very good game on its own merits and not a tech demo, came to change a lot of stuff, learned from that long Research and Development process. The return to the Half-Life universe for Valve was also a return on setting new standards like the original game did, and that is recognizable even in the game structure, which starts very much like a walking simulator, turns into a first-person shooter, then an investigation puzzle, changes into a creepy survival horror like Alien: Isolation, then into a war game, has melée sections with special powers like fighting games and so on. It really goes into a lot of genres to tell how it should be done in those cases.

So, to illustrate what I am saying; almost all games before Half-Life: Alyx have very little physicality on them. For the perspective, Alyx was announced November 21, 2019 – when Valve started showing their design principles in public – and launched in March 2020. Before that, a few VR-only tactile games like Sairento VR, The Thrill of the Fight and GORN did exist, but they were invariably short experiences for a few genres that already use physics engines even on flatscreen. The deep, high production, long games like Fallout 4 VR (2017), Borderlands 2 VR (2019) and Skyrim VR (2018), adapted from their pancake versions, might still be some great fun to play, but they clearly, utterly lack the tactile sensation of Alyx, the interactivity with people and objects, your hand touching and bumping through objects instead of just, like a ghost, passing through them. That became so evident that in the case of Skyrim there is even a mod called VRIK Player Avatar for the game to be more immersive and tactile, with full body representation, body slots to attach weapons and items, and gestures to cast spells and change weapons or outfits. It works on Linux but in a kind of convoluted way and might need a custom build of Proton. You can expect an article describing the process here on Boiling Steam soon, of course.

Conversely, after Alyx announcement a number of more involved, complex games purporting deep physics and interactivity started appearing. The Walking Dead: Saints and Sinners (Jan 2020) might have been the first one of the kind and it shows lots of design principles akin to Alyx, although it doesn’t have a big quantity of interactive objects. Released in July 2020, Karnage Chronicles firmly relies on physical acts like rewinding an energy bow to be able to shoot and bringing edible objects to your mouth to regain health. An interesting case study is the VR-only RPG The Wizards, which was released in March 2018, and its sequel The Wizard - Dark Times, released post Alyx on June 2020: it is a much better game, purporting a “reworked gesture-based spellcasting system and new environment interactions” as said on its steam page, clearly showing the Alyx influence.

A few of the tropes Alyx brought to the spotlight (not all of them invented by Valve, of course):

- If your hand collides with solid objects or walls, it doesn’t pass through, it is shown touching it only. This works without breaking the immersion because of the rubber hand illusion, where you “feel” the visible hand as yours even if it is in a different position.

- If your body collides with solid objects or walls, your vision is occluded with an unpleasant yellow tint, and you are only able to backtrack.

- To climb a ladder you have to grab it and push the steps towards yourself (although there is a teleport option you could alse use)

- To store and retrieve inventory items, you have easily visible assigned slots in your body – in the case of Alyx, the wrists. Some games like Walking Dead: Saints and Sinners employ a backpack which you can get by extending your arms to your back and “grabbing” it.

- You can perform some random actions that would be possible in the real life with the objects - if you grab a hat, you should be able to put it in your head and it will stay there. Curiously enough, there are pairs of glasses you encounter on Alyx which you cannot wear, but that might be because you would just bump your controllers on your headset if you attempted it (and I did!).

- There is no automatic reloading – there is a somewhat complex set of actions you must make which mimic the real-life physical operation. This brings a new type of satisfaction to VR games when you internalize these movements enough to perform them very quickly.

- Pointing to a distant object and making a pulling gesture with a button delivers it on your hand. Use the force, Luke!

- You have to turn handles and knobs, raise windows, push doors, throw stuff and type on keyboards with your hands and fingers; as a rule of thumb, simple button actions are avoided for the sake of immersion.

- For heavy objects the two hands might be required.

- You get variable vibration feedback for simulating touch, specially concerning the resistance of objects to motion.

There are loads of new games following these tropes appearing on Steam, almost always working on Linux. The future is bright indeed (if the Oculus Quest success and the move to mobile does not spoil it for us)!

My Personal VR Aftermath

If there is one downside of getting so deep into VR is being spoiled by it, so your joy on pancake games is affected. I have been an immersion junkie for a long time now, and at the time my VR kit arrived (April 2020), I was playing three fantastic immersive games: X4 Foundations, Metro: Exodus and Kingdom Come: Deliverance. All first-person games, all of them immersive… for a pancake game. I was so busy for the weeks after the kit that I haven’t even realized I had stopped playing them – until I eventually tried to resume my gameplay. It was an unsettling sensation – it seemed the flat 3D of the screen could not deceive my senses anymore, and the distance from the monitor made me feel very far from the action. I loved these games but I could not get myself engaged on them for more than 15 minutes each time I tried.

For the incoming months, this trend even increased. Although I still played non-VR games, these were non-immersive like isometric RPGs and 2D games. My next steam purchases would be mostly VR titles, and in the latest steam sales all 20 games I bought had VR.

![]()

That’s why I haven’t yet bought Cyberpunk 2077, Red Dead Redemption 2, Death Stranding and so many immersive AAA games that now work on Linux. I know I will barely engage on them, if at all, even though I am sure they are excellent games. So, I do try and satiate my hunger for these titles with similar games. For Cyberpunk, I will probably buy Low-Fi when it’s out (there are alpha versions on itch). For the others… well, time will tell.

I cannot say that this spoiling will happen to everyone that gets adapted to VR – as for anecdotal evidence, some friends which use VR a lot still play pancake games –, but that might hint that if you embark on this adventure, you might soon miss the joy of your game collection, so take that as a cautionary tale. On the other hand, you’ll be able to enjoy a growing collection of new ones…

VR Tools, Add-ons and Utilities

As I already say, many of us use Linux because of the power it puts in our hands. And I already mentioned TurnSignal and steamvr-tools. Tools like these are essential to be able to exercise that power, to really own the game instead of merely renting it, to be able to make what you see fit of it. But does Linux have a good variety and amount of such applications?

Unfortunately, not.

That is expected, actually. I already said we’re a niche of a niche – when esoteric technologies get to Linux, they always start slowly, because there’s no one using it. This very article is trying to improve on this problem by elevating the mindshare of VR technologies.

Windows users have librevive and VorpX. Librevive helps by bridging the Oculus proprietary API to OpenVR/OpenXR, thus enabling the users to play Oculus-exclusive games on their Vive or Index. But since the Oculus API has low level parts (not emulated by wine) and is needed for this bridging, it won’t work on Linux. Conversely, vorpX is an expensive proprietary DLL injector that adapts the visuals and inputs of a selection of games to make them playable in VR, and it is flexible enough that it allows user recipes for unsupported games.

Besides that, they have creative adaptations like MotherVR, an Alien: Isolation specific injector that reuses some hidden VR code and assets from the original game to offer a competent VR implementation. Although WINE in theory would support these injections, I could not make it work on Linux, nor do I know anyone who did. ReclaimerVR is a similar tool for the Master Chief Collection.

We do not have these, specially the librevive functionality. But there has been some progress, and some notable individuals which have contributed some tooling. First of all, there is a tool called vr-video-player that despite its name, can not only be used to play 3D movies on the headset, but also grab any window with SBS (side-by-side) panels and project them into VR.

Fortunately, the already well known vkBasalt supports Reshade post-processing injectors, which fundamentally alters the way a game renders on screen. And this can be used on Proton!

The procedure of setting up Reshade for SBS rendering, plus calling vr-video-player to project on the headset is quite cumbersome but there is a wonderful set of utilities that work on Steam called steamtinkerlaunch. Many people might already know this tool for pancake games, but it has a semi-automated way to make Proton games work in the headset. Just remember, though, that the stereoscopic vision is just one part of the equation, the input for head tracking must also be synchronized and the game certainly won’t offer support for the haptic controls.

This is also true for Windows, though – as polished as vorpX is, it cannot fix a game that was not designed for VR. You can be dazzled by installing the first-person mod on the Witcher 3 and then running vorpx to play it in your headset, but you will still be using the same pancake controls.

Nevertheless, it’s in our future projects to better explain how to use steamtinkerlaunch and adapt your games to be in VR.

Other interesting utilities include the multiplatform OVR Advanced Settings, which is also free on Steam and lets you fine-tune your VR configuration. This is an essential utility!

I could not find any functional tool for VR streaming on Linux, but it just happens that XRDesktop allows overlaying things on the display and Linux streamer Corben78 uses it along twitch game integration to make compositions and show himself in third-person view while playing games. Highly recommended, and dude is specially impressive by enduring 4+h of physical exercise nonstop.

And finally, for a page that tries to be up-to-date on VR resource on Linux, there’s the gitlab-hosted VR on Linux. Not a tool but useful nevertheless.

References:

The history of VR- https://virtualspeech.com/blog/history-of-vr

Timewarp (and reprojection** explained - https://uploadvr.com/reprojection-explained/

Interview with Valve developers about Half-Life: Alyx - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cRVXhA0-TI4

Notes:

- No Man’s Sky VR mode is currently not working on Linux, although it did in the past.

- Fallout 4 VR currently needs SteamVR stable to be able to input your name in the starting section.

- Until You Fall is currently not working on Linux, although it did in the past.

- SEGA Mega Drive and Genesis Classics does not work in VR on Linux currently.

- Unless stated otherwise, ALL VR games mentioned on this article work on Linux.

Credits

- A few friends from various places, from forums to Steam, contributed with explanations and testimonies on various headsets on Linux. I’d like to thank TheRiddick, Corben78, Julius, jens, SirUpdatesaLot and a few others which preferred to remain anonymous. I would also like to thank the staff of BoilingSteam for the warm reception to the team.